TASC Notes - Part 8

These are the notes summarising what was covered in The Art and Science of CAP part 8, one episode in a mini series with Daniel Hutzel to explore the philosophy, the background, the technology history and layers that support and inform the SAP Cloud Application Programming Model.

For all resources related to this series, see the post The Art and Science of CAP.

This episode started with me rambling slightly more than usual as I attempted to locate Daniel, but suddenly, as if by magic, the shopkeeper appeared.

(This is the usual start scene from Mr Benn, one of my favourite TV programmes as a young child in the early 1970's, and the phrase above has stuck in my mind ever since).

We took slightly longer to review and discuss the notes on the previous episode (part 7), as there were some super eye openers that were worth revisiting, not least the beautiful reveal of the parallel between functional programming and aspect oriented techniques, and the proper way to extend entities.

The relational model

At 23:50 Daniel dives back into where we left off in the previous episode, to dwell a little on some important theory in the form of the Relational Model.

At first glance, this seems like hard and somewhat dry theory, but it's important for the foundations of CAP, and while it may not help us in our day to day application development work, it will help us build a solid basis of understanding. It's equally if not more important for Daniel and the CAP team building out the framework to ensure that - in and of itself - CAP follows sensible principles that have come before, that have arisen from the hard graft of our large-brained computing predecessors.

In particular, Daniel wanted to ensure that the extensions to SQL making CQL a superset, in particular nested projections and path expressions, still conformed to the Relational Model approach to data modelling, storage and retrieval.

What is a relvar?

I struggled initially to properly grok the meaning and significance of the term "relvar". Building on the context ably set by Daniel in this episode, I found my curiosity getting the better of me (as it always does) and embarked upon a voyage of discovery, starting at that Relational Model Wikipedia page.

What moved me closer to understanding "relvar" was to realise that the terms I've always used for artifacts and concepts in relational database systems and operations ... are not entirely formal. A relvar, short for relation variable, is from the strictly formal terminology set where:

- tables (or views) are called relations

- a table's columns (fields) are called attributes

- records (or rows) are called tuples

Consequently, a name referring to a table (a relation), such as "Customers", or "Foo" is called a relation variable. This is clarified in the Wikipedia page with reference to Date, thus:

At any given time, all information in the database is represented solely by values within tuples, corresponding to attributes, in relations identified by relvars

(emphasis mine).

Moreover, the term "relational variable" was introduced in a work by Date and Darwen: Databases, Types, and The Relational Model: The Third Manifesto.

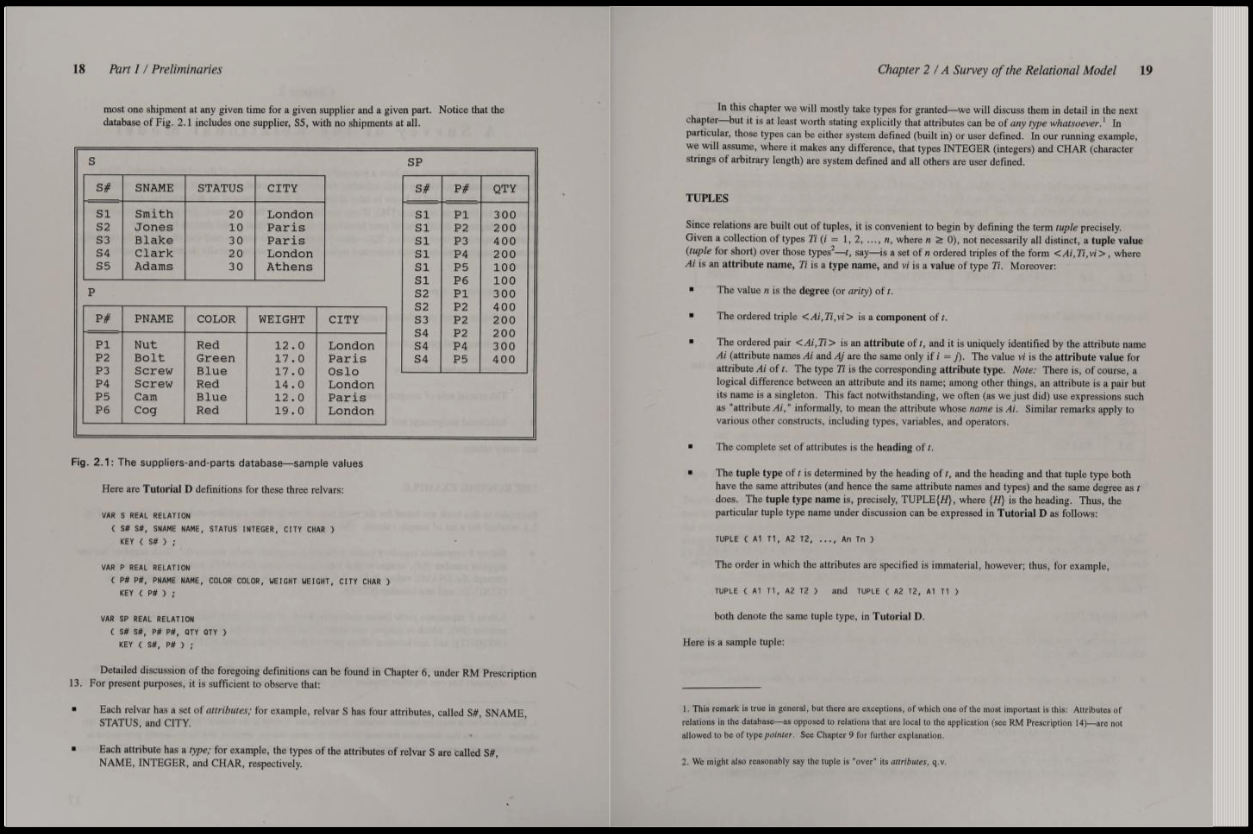

This work is available online thanks to the wonderful Internet Archive's online lending library, and in Chapter 2 "A Survey of the Relational Model" we see a definition of a sample relation (table) S to hold supplier information:

VAR S REAL RELATION

{ S# S#, SNAME NAME, STATUS INTEGER, CITY CHAR }

KEY { S# };This definition helps cement the concept of a relvar through the VAR "assignment" or "association" of a relation definition ({ ... }) to a name S. So we can think of a relvar as a symbol that can reference different values at different times, where the values are actually what we'd normally refer to as "tables" or "views", formally called relations, and the data that they contain, and that we can query.

Exploring in SQLite

Digging in a little more, Daniel, ever local-first, opens the SQLite prompt, which is quite like a REPL itself. He defines a table (relation), and then a view (also a relation), and then uses SQL to add data (a tuple) to the table:

sqlite> create table foo ( a,b,c );

sqlite> create view bar as select * from foo;

sqlite> insert into foo values ( 1,2,3 );While a view is a projection, it is still in essence a table, a relation, in that it contains data.

Next, Daniel summons the god of meta, with:

sqlite> select * from sqlite_schema;

table|foo|foo|2|CREATE TABLE foo ( a,b,c )

view|bar|bar|0|CREATE VIEW bar as select * from fooThis is a little easier to comprehend if we look at the SQLite schema table reference:

CREATE TABLE sqlite_schema(

type text,

name text,

tbl_name text,

rootpage integer,

sql text

);In fact, we can use the SQLite REPL command .headers on1 so that output like this is simpler to understand:

sqlite> .headers on

sqlite> select * from sqlite_schema;

type|name|tbl_name|rootpage|sql

table|foo|foo|2|CREATE TABLE foo ( a,b,c )

view|bar|bar|0|CREATE VIEW bar as select * from fooHaving examined the definitions of the fields in sqlite_schema, we can interpret these two records (or tuples, to use formal parlance) as:

foo --> table(CREATE TABLE foo ( a,b,c )bar --> view(CREATE VIEW bar as select * from foo

where the --> arrows indicate reference, associating the relvars with the relations.

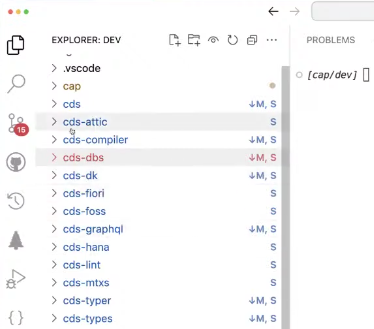

Local development, submodules and workspaces

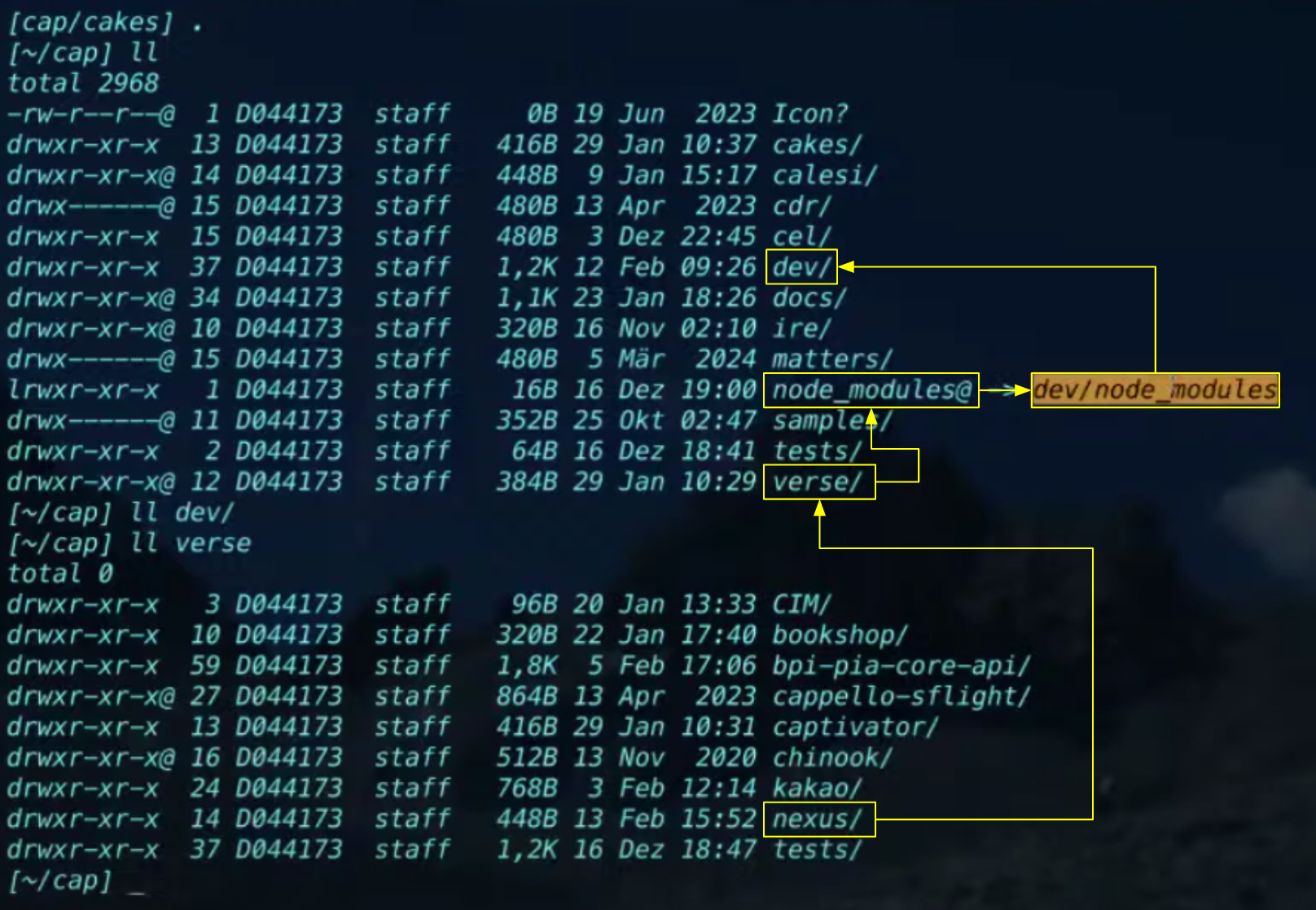

While we've talked briefly about monorepos previously in this series, it's worth revisiting for a second here too, where at around 29:30 Daniel outlines his local development setup which is based on an "umbrella" Node.js project using submodules and workspaces.

The huge advantage to this approach is that you have everything at hand, locally. You can read more on the approaches used:

- Working with submodules

- NPM workspaces (also covered in the recent series on CAP Node.js Plugins - see Creating our own plugin package in the notes to part 1 of that series)

Daniel highlights a particular advantage of embracing workspaces: not having to connect to the cloud when building a constellation of interdependent microservices; rather, everything can be developed locally. "Like having your own private NPM registry", too.

And in explaining how he works with application projects in the context of his development "environment" (directory and file structure), I learned today how Node.js searches for modules: not just in the project's node_modules/ directory, but "upwards" through the directory hierarchy too. This is explained nicely in Loading from node_modules folders, and we can see how that works in Daniel's context here:

Daniel pointed out here that

cdr/was the very first implementation of CAP from 2016, where he was working along on it; and it stands for "CDS Done Right" :-)

Here, for the example application repository "nexus" cloned into the verse/ directory, Node.js will search for modules in a node_modules/ directory:

- in the

nexus/directory itself (not found) - in the containing

verse/directory (also not found) - in the directory that contains

verse/(which iscap/)

At this point, because of the symbolic link (identified in the screenshot as node_modules@) that points to the node_modules/ directory inside of the dev/ directory, the CAP modules are found and loaded, from exactly where Daniel wants them loaded, from his local copy of whatever version of CAP he's working on or managing at that time.

$HOME/

|

+- cap/

|

+- dev/

| |

| +-- node_modules/ --+

| |

+- node_modules@ ------+

|

+- verse/

|

+- nexus/Node.js, unlike dogs ... according to Big Al, can look up.

To underline the utility and convenience of this structure and approach, Daniel starts the cds REPL with the --run option (shortened to -r) specifying ... the package (module) name, not the directory name:

[cap/cakes] cds r -r @capire/bookshop

Welcome to cds repl v 8.8.0

[cds] - loaded model from 5 file(s):

../dev/cap/samples/bookshop/srv/user-service.cds

../dev/cap/samples/bookshop/srv/cat-service.cds

../dev/cap/samples/bookshop/srv/admin-service.cds

../dev/cap/samples/bookshop/db/schema.cds

../dev/cds/common.cds

Note the locations of each of these five loaded files!

Queries declare relations!

Daniel started the cds REPL at around 36:45 with the "bookshop" service to have something concrete with which to illustrate the close proximity of CAP (and CDS and CQL in particular) to the formal relational model.

Consider this:

await cds.ql `SELECT ID,name from Authors`Here, Authors is the name of an entity, in CDS model terms. It also happens to be a table (at the persistence layer level).

But critically, this is (almost) a relvar.

What's returned ... is a set of tuples (four, in this case):

[

{ ID: 101, name: 'Emily Brontë' },

{ ID: 107, name: 'Charlotte Brontë' },

{ ID: 150, name: 'Edgar Allen Poe' },

{ ID: 170, name: 'Richard Carpenter' }

]each containing the attributes ID and name.

Now consider this:

await cds.ql `SELECT ID,name,books.title from Authors`Spot the books.title path expression?

This is what's returned:

[

{ ID: 101, name: 'Emily Brontë', books_title: 'Wuthering Heights' },

{ ID: 107, name: 'Charlotte Brontë', books_title: 'Jane Eyre' },

{ ID: 150, name: 'Edgar Allen Poe', books_title: 'Eleonora' },

{ ID: 150, name: 'Edgar Allen Poe', books_title: 'The Raven' },

{ ID: 170, name: 'Richard Carpenter', books_title: 'Catweazle' }

]The result is another set of tuples, where the path expression has been materialised into just another attribute books_title (regardless of any SQL details going on under the surface to make this happen). This result set is ... a relation.

But it's not a relation pre-declared like S (see What is a relvar? earlier); it's a relation declared ad hoc with the query.

In SQL (and consequently CQL): queries describe (declare) relations.

So, thinking back to the concept of relvars, is this query the relvar?

[

{ ID: 101, name: 'Emily ...

{ ID: 107, name: 'Charlo...

SELECT ----> { ID: 150, name: 'Edgar ...

ID,name,books.title { ID: 150, name: 'Edgar ...

from Authors { ID: 170, name: 'Richar...

]Almost, but not quite. But we can store that query in a variable2:

myAuthors = cds.ql `SELECT ID,name,books.title from Authors`and then that variable myAuthors is the relvar:

myAuthors [

| { ID: 101, name: 'Emily ...

V { ID: 107, name: 'Charlo...

SELECT ----> { ID: 150, name: 'Edgar ...

ID,name,books.title { ID: 150, name: 'Edgar ...

from Authors { ID: 170, name: 'Richar...

]And if we use await to reify that relvar, we get the relation.

Relations, attributes and values

When reifying a relation you're essentially expecting a set of tuples containing values. What happens when the attribute projection of an element expressed in a query doesn't have a value? What does that even mean? Well, Daniel illustrates this next by digging in a little deeper to the managed associations between Books and Authors here.

But let's back up a second to re-familiarise ourselves with the Books and Authors entities in the bookshop sample. Here's a very simplified pair of entities in a simple-schema.cds file:

entity Books : {

key ID : Integer;

title : String;

author : Association to Authors;

}

entity Authors : {

key ID : Integer;

name : String;

books : Association to many Books on books.author = $self;

}The to-one managed association in Books causes a foreign key style element author_ID to be generated automatically. The to-many association in Authors, in contrast, does not.

If you think of these associations in terms of "left" and "right", to-one associations have the pointer value (the foreign key) on the left hand side, the "source" side, and to-many associations have the value on the right hand side, the "target" side.

This can be seen clearly if we ask the compiler to show us the DDL, for example:

$ cds compile --to sql simple-schema.cds

CREATE TABLE Books (

ID INTEGER NOT NULL,

title NVARCHAR(255),

author_ID INTEGER,

PRIMARY KEY(ID)

);

CREATE TABLE Authors (

ID INTEGER NOT NULL,

name NVARCHAR(255),

PRIMARY KEY(ID)

);We are also likely to spot this in when creating CSV data:

$ cds add data --out data && head -1 data/*

Adding feature 'data'...

Creating data/Authors.csv

Creating data/Books.csv

Successfully added features to your project.

==> data/Authors.csv <==

ID,name

==> data/Books.csv <==

ID,title,author_IDWe can see the author_ID field in the header of the Books.csv file. There is no equivalent in the Authors.csv file.

With this in mind, let's turn back now to what Daniel shows us, which starts with an innocent-enough looking query:

await cds.ql `SELECT ID,name,books from Authors`What's returned, however, is not quite what we might be expecting:

[

{ ID: 101, name: 'Emily Brontë' },

{ ID: 107, name: 'Charlotte Brontë' },

{ ID: 150, name: 'Edgar Allen Poe' },

{ ID: 170, name: 'Richard Carpenter' }

]Related but not the same as the request for books.title made earlier, we're now asking for books. What is that? It's the representation of the entire to-many managed association ... which does not (can not, really) have a (scalar) value.

In contrast, regard this query on the Books entity:

await cds.ql `SELECT ID,name,author from Books`Here, we're still requesting values for an association (author) but this time it's a to-one association, which does have a scalar value that can be surfaced. Yes, the value of the foreign key, i.e. the value of author_ID:

[

{ ID: 201, title: 'Wuthering Heights', author_ID: 101 },

{ ID: 107, title: 'Jane Eyre', author_ID: 107 },

{ ID: 150, title: 'Eleonora', author_ID: 150 },

{ ID: 150, title: 'The Raven', author_ID: 150 },

{ ID: 150, title: 'Catweazle', author_ID: 170 }

]In the context of SQL being the real world representation of relations, in the end, we also can think about how foreign keys, the "coupling" in to-one association, become the values of the references that are surfaced in reifying such ad hoc relations. Before that, associations are "just pointer-shaped ideas".

Postfix projections and set theory

Now we're more comfortable with the concept of "pointers" in the relational model and how it is respected in CAP, here's something that will blow your mind in a hopefully similar way to which it was in the previous part where the parallel between functional programming, aspects and entity extensions was revealed (see the Reflections in CDS modelling section).

First, consider the alternative way of expressing the prefix projection style query SELECT ID,name,books from Authors - the so-called postfix projection style of expression:

await cds.ql `SELECT from Authors { ID, name, books }`At one level, we might think of this as mere syntactic sugar. But with the relational model theory in mind, we can adopt this style of expression as a better way of thinking about the model in general.

Adding an arrow to represent the pointer in this relationship:

Authors -> { ID, name, books }allows us to think about this, with respect to Authors, as follows (in Daniel's words): "from all your children (tuples), we want these attributes".

So far so good. But we're now in a better position to project that thinking to the next level, thus:

Authors -> { ID, name, books -> { ID, title } }While in relational model terms Authors and books are relvars, in terms of set theory they are sets, and the "books for the current Author" is part of that theory, as is how CAP extends SQL to CQL in that context to allow for such nested projections relations3 and expressions thereof.

Behold:

await cds.ql `SELECT from Authors { ID, name, books { ID, title } }`which produces:

[

{

ID: 101,

name: 'Emily Brontë',

books: [ { ID: 201, title: 'Wuthering Heights' } ]

},

{

ID: 107,

name: 'Charlotte Brontë',

books: [ { ID: 207, title: 'Jane Eyre' } ]

},

{

ID: 150,

name: 'Edgar Allen Poe',

books: [ { ID: 251, title: 'The Raven' }, { ID: 252, title: 'Eleonora' } ]

},

{

ID: 170,

name: 'Richard Carpenter',

books: [ { ID: 271, title: 'Catweazle' } ]

}

]Spot the nesting also in the result set - there are two books from Mr Poe, and (to use relational model terms) both are returned in the set of tuples for the books attribute projected from the pointer attribute in the corresponding Author tuple.

The universe of discourse and correlated subqueries

Rounding out this mind-expanding episode, Daniel notes that the concept of the "universe of discourse" (alternatively called the domain of discourse), the set of entities over which values may range, is an appropriate theoretical construct in which to think about how these values (from the nested projections) exist.

And where the rubber meets the road, how are such expressions materialised? How does CAP go from the value of a relvar (which all along, here, has been the query expression) to the ad hoc relation which it represents?

By means of correlated subqueries.

But what are they and where are they used?

Well, asking the runtime to give us an insight into what it's doing, specifically with respect to SQL, we get a glimpse. Restarting the cds REPL at around 50:02 with the DEBUG environment variable set appropriately, Daniel demonstrates:

[cap/cakes] DEBUG=sql cds r -r @capire/bookshop

> await cds.ql `SELECT from Authors { ID, name, books { ID, title } }`

[sql] - BEGIN

[sql] - SELECT json_insert('{}','$."ID"',ID,'$."name"',name,'$."books"',books->'$') as _json_ FROM

(SELECT Authors.ID,Authors.name,(SELECT jsonb_group_array(jsonb_insert('{}','$."ID"',ID,'$."title"',

title)) as _json_ FROM (SELECT books.ID,books.title FROM sap_capire_bookshop_Books as books WHERE

Authors.ID = books.author_ID)) as books FROM sap_capire_bookshop_Authors as Authors)

[sql] - COMMIT

[

{

ID: 101,

name: 'Emily Brontë',

books: [ { ID: 201, title: 'Wuthering Heights' } ]

},

{

ID: 107,

name: 'Charlotte Brontë',

books: [ { ID: 207, title: 'Jane Eyre' } ]

},

{

ID: 150,

name: 'Edgar Allen Poe',

books: [ { ID: 251, title: 'The Raven' }, { ID: 252, title: 'Eleonora' } ]

},

{

ID: 170,

name: 'Richard Carpenter',

books: [ { ID: 271, title: 'Catweazle' } ]

}

]This is what I call the "swan effect": what we see is graceful elegance, what we don't see is the furious paddling under the surface.

A mute swan, picture courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The graceful elegance of SELECT from Authors { ID, name, books { ID, name } } is only possible because of the furious paddling going on under the covers - here's that SQL statement from the DEBUG output in a more readable format:

SELECT

json_insert(

'{}', '$."ID"', ID, '$."name"', name,

'$."books"', books -> '$'

) as _json_

FROM

(

SELECT

Authors.ID,

Authors.name,

(

SELECT

jsonb_group_array(

jsonb_insert(

'{}', '$."ID"', ID, '$."title"', title

)

) as _json_

FROM

(

SELECT

books.ID,

books.title

FROM

sap_capire_bookshop_Books as books

WHERE

Authors.ID = books.author_ID

)

) as books

FROM

sap_capire_bookshop_Authors as Authors

)Briefly:

- Retrieval of

booksis achieved via a SQL subselect (SELECT Authors.ID, Authors.name ( the-subselect ) as books FROM sap_capire_bookshop_Authors as Authors) - SQL subselects are normally allowed only when the result is scalar

- But CAP maps nested projections into SQL subselects that return a set, i.e. that are not scalar

- The set that is to be returned is "turned into" a scalar (thus legitimising this SQL subselect) with the

jsonb_group_arrayfunction4 which creates a stringified JSON structure - Further up the call stack, above the execution of this query, this stringified JSON is turned back into the set that is, in reality, the shape, or form, in which we expect the "real" value to exist

By the way:

- The "correlated" part of this SQL subselect (subquery) is how the inner relation (

WHERE Authors.ID = books.author_ID) refers to a value in the outer query (SELECT Authors.ID)

A closure Easter Egg

This is where this episode ends, having imparted a metric tonne of wonder and understanding both from the art and the science side of CAP. But did you notice? Daniel wasn't even done at this point - he left us with a small Easter Egg here, in showing us the nature of correlated subqueries.

What is that Easter Egg? Well, we've previously learned how some functional programming concepts such as pure functions play a key role in the layers that inform CAP's design and implementation. Well, here's another: did you notice how correlated subqueries are exactly like closures (a technique for implementing lexically scoped name binding in languages with support for first class functions)? Let me know in the comments what you think.

As always, thanks for watching, and especially thanks for reading this far. See you in the next episode!

Footnotes

-

Notice how these REPL commands have a similar structure (they begin with a

.) to the Node.js / cds REPL. -

Remember, queries are first class citizens - see Functions as first class citizens in SICP Lecture 1A.

-

For more on nested projections, you might enjoy Turning an OData expand into a cds.ql CQL query with a projection function in CAP.

-

jsonb_group_arrayis an array aggregate function (thebin the name represents the "binary" version which is more efficient).

- ← Previous

TASC Notes - Part 7 - Next →

TASC Notes - Part 9