TASC Notes - Part 7

These are the notes summarising what was covered in The Art and Science of CAP part 7, one episode in a mini series with Daniel Hutzel to explore the philosophy, the background, the technology history and layers that support and inform the SAP Cloud Application Programming Model.

For all resources related to this series, see the post The Art and Science of CAP.

This episode started with a review of the previous episode (part 6), based on the notes for that episode. We continued to look back more generally over the previous episodes to pick out the main themes around which we wove a (hopefully) coherent story:

- Domain-driven design

- The importance of modelling

- Aspect-oriented programming

- Artistic & scientific principles

During this review, at around 18:25, it was almost inevitable that we revisited the Class vs Prototype conversation, dwelling on the differences, and the importance of prototypical inheritance (the power of which is also reflected in the concept of mixins). But before we got to diving into that, we took a quick detour to revisit the theme of code generation.

A quick review of some bad practices and what CAP brings

We talked about code generation, and how and why it appears in the Bad Practices topic in Capire. This time Daniel reminded us of today's popular context of serverless and functions-as-a-service where codebase size and startup times - two areas where code generation cause more problems than they solve - are critical. Moreover, an approach that CAP also takes here is what one could only describe as at the opposite end of code generation and the staleness that inevitably accompanies that - dynamic interpretation of the models at run time.

Talking of staleness and "glue code" (technical non-domain code), another key philosophy driving CAP's design and realisation here is the idea that application developers should concentrate on developing the application. They should not be working on technical aspects of bringing that application to bear - tenant isolation, database management, security, protocol-level service integration and so on.

In fact, the entire idea of CAP's Calesi Pattern (CAP-level service integration) fits squarely into the space that this philosophical approach is carving out for us - the provision of CAP client libraries for BTP platform services that are designed to drastically reduce boilerplate and purely technical code.

Another aspect of why keeping the code inside the framework is important is eloquently expressed by Daniel: as builders of enterprise applications, we have to ensure that our code scales, and that our teams and the output from those teams can scale too.

Taking care of the important non-domain-specific aspects of building such enterprise applications not only removes the tedium but also reduces the chance for error and minimises the possibilities for varying and ultimately chaotically different approaches across different teams (think about how SAP-delivered UI5 based Fiori apps have standard layouts and MVC patterns, and why Fiori elements came into being).

Revisiting some of CAP's solid science foundations

At around 25:20 Daniel shared a biography slide from a deck that he'd compiled for a recent presentation on CAP at the Hasso Plattner Institute.

I couldn't help notice Daniel's pedigree from that biography slide; I mean, many of us already know Smalltalk runs through his veins, and perhaps knew, or at least suspected, that he has had enough experience1 with Java and JEE to ensure that CAP exudes good practices and eschews bad ones ... in the right way ;-)

And I was delighted to learn that he also has been touched by NeXTSTEP - an object-oriented OS that also happened to sport a graphical desktop manager that is one of my favourites (and which lives on in the form of Window Maker). I'm already assuming that you realise that NeXTSTEP was created for the machines upon which the Web was invented - it was on a NeXTcube that Tim Berners-Lee wrote the first versions of Web client and server software.

Daniel jumps from Smalltalk to Lisp (the latter influenced the former) which is the "hero language" of functional programming, one of the key science pillars of CAP. It's hard to sum up decades of computing and computer science here, but I can sleep easy knowing that the good parts are in CAP; and those parts that were ultimately discovered to be not so good ... are not.

In the abstract-all-the-things mania of the 90's we had CASE and UML (and the corresponding code generation machinery that went with that) and by and large this has now been shown, over and over again, to be a noble but essentially wrong direction.

Ironically, or at least in stark contrast, we have functional programming and the simplicity of treating data as data (passive), which in turn allows us to think about immutability. And things that cannot move ... cannot break.

Not only that, but such qualities allow us to think about processing large quantities of data with simple pipelines, such as MapReduce, which is a scalable and relatively efficient way of analysing data in a chain of steps that are each horizontally scalable (and yes, the name comes from two classic functions map and reduce2 that are building blocks in many functional programming approaches).

Core functional programming tenets such as immutability and the related concept of pure functions, i.e. those that are side-effect free, principles that allows mechanisms such as function chains (such as ones used in MapReduce) are consequently found in CAP too:

On the topic of passive data, Daniel relates the story of an esteemed colleague extolling the virtues of non-anemic objects, while Daniel himself takes the opposite approach. While the adjective anemic is an established one, it is a pejorative description based on a viewpoint held not least by luminaries such as Martin Fowler 3, and I suggest we use a different, more positive term for what we're striving for here. "Pure objects", anyone?

Anemic, or pure objects, are almost a prerequisite for late binding and aspect oriented techniques.

Prototype based system examples

Riffing on that last point, championing the prototype based inheritance model over the class based one, Daniel opens up one of our (now) favourite developer tools - the cds REPL - to give an example, which I'll try to summarise here.

First, a "class" Foo is defined, and an "instance" created:

> Foo = class { bar = 11; boo(){ return "Hu?" } }

class { bar = 11; boo(){ return "Hu?" } }

> foo = new Foo

Foo { bar: 11 }The boo "method" is available on foo:

> foo.boo()

Hu?Note that so far I've used double quotes around "class", "instance" and "method" here.

Next we can create Bar as an child "class" of Foo:

> Bar = class extends Foo {}

class extends Foo {}At this point "instances" of Bar have both the bar property and the boo "method" available:

> bar = new Bar

Bar { bar: 11 }

> bar.boo()

Hu?And here's what's really going to wake you up: THERE IS NO CLASS. Moreover, bar is not an instance either (in the sense that we might understand or expect from the Java world, for example).

It's prototypes all the way down.

What's great is that we can employ aspect oriented approaches here, in that even if we're not the owner of Foo, we can add an aspect, a new behaviour to it, in a totally "late" way:

> Foo.prototype.moo = function(){ return "Not a cow" }

function(){ return "Not a cow" }And through the syntactic sugar and class machinery here, we see that bar even now has access to this new behaviour:

> bar.moo()

Not a cowFinally, to underline how fundamental the prototype mechanic is here, Daniel creates another "instance" of Foo (car), but perhaps not how you'd expect:

> car = { __proto__: foo }

Foo {}

> car.bar

11

> car.boo()

Hu?Boom!

Reflection in the cds REPL

Directly after this, at around 38:56, Daniel jumps into the cds REPL to demonstrate how much of this is also reflected in CDS model construction. He almost immediately reaches for the relatively new .inspect cds REPL command (which we saw both in a previous episode of this series and also in part 2 of the mini-series on CAP Node.js plugins), which in turn reveals a whole series of LinkedDefinitions.

These LinkedDefinitions are iterables, and if you want to know more about how to embrace them, for example using destructuring assignments or the for ... of and for ... in statements see the Digging deeper into the Bookshop service section of the notes to part 2 of this series.

Reflection in CDS modelling

Launching from the fundamental prototype approach which we've explored now, Daniel connects the dots for us by revisiting some common4 aspects (managed and cuid) to show how the prototype approach brings the ultimate in aspect-based flexibility.

In particular, he relates a project situation where the managed aspect wasn't quite enough for what was required - the domain model design required the ability to store a comment on what was changed, in addition to actually tracking that it was changed.

And guess what? In exactly the same way as moo was added to Foo as a late injected aspect earlier, despite the lack of actual "ownership" of Foo:

Foo.prototype.moo = function(){ return "Not a cow" }... the project was able to realise that design by adding the new element (let's use boo to keep things simple and show the parallel) to the managed aspect, again, despite the lack of actual "ownership" of that aspect or its wider context (@sap/cds/common):

extend managed with {

boo : String;

}This is art and science coming full circle in a beautiful parallel, and was well worth revisiting since Daniel talked about it earlier in the series, and which I subsequently blogged about in Flattening the hierarachy with mixins.

This time around though, we are better informed to grok how CDS modelling reflects the fundamental building blocks of the computer science upon which it is built, and the obvious relationship bursts forth from the editor.

Extensible means extensible

Following this completed circle, Daniel then expands on the extension by showing that effectively anything is possible, by specifying that the element in the extension should actually be a relationship to a complex object. On the way, we are taught how to think in flexible rather than rigid terms, using CDL features that we actually already know.

The starting scenario is that the "bookshop" service has a couple of entities Books and Authors, each of which are extended via the managed aspect:

entity Books : managed {

descr : localized String(1111);

author : Association to Authors @mandatory;

...

}

entity Authors : managed {

key ID : Integer;

name : String(111) @mandatory;

...

}With this addition of an element via the extension to the managed aspect:

extend managed with {

boo : String;

}each of Books and Authors would have this boo element too.

The wrong way

But what happens when that element should be something more complex, like a change list:

entity ChangeList : {

key ID : UUID;

timestamp : Timestamp;

user : String;

comment : String;

}That looks reasonable, so let's modify the additional element to relate to this. Something like:

extend managed with {

changes : Composition of many ChangeList on changes.book = $self;

}The problem with this is it's both brittle and inflexible as we now also need to add an element in the ChangeList entity to be a back pointer:

entity ChangeList : {

Book : Association to Books;

key ID : UUID;

timestamp : Timestamp;

user : String;

comment : String;

}Oops - and also one for Authors:

entity ChangeList : {

Book : Association to Books;

Authors : Association to Authors;

key ID : UUID;

timestamp : Timestamp;

user : String;

comment : String;

}Where will this end? Well, not only is it brittle and inflexible ... it's also wrong, because this aspect extension is now inextricably tied up with references to random entities to which the aspect itself has been applied.

And how could that ever work, when you factor time into the equation? Who knows what future entities you might have and want to extend with the managed aspect? And let's not even think about trying to address this with polymorphic associations. And not even coming up with a generic parent : <sometype> is going to work either.

As my sister Katie is fond of saying: How about "no"?.

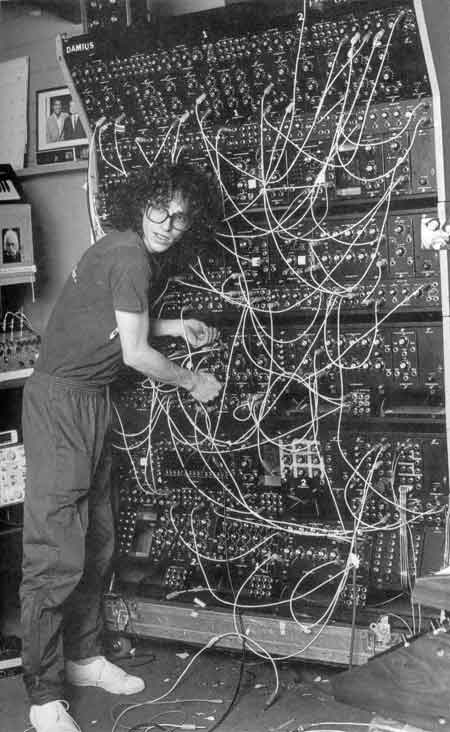

If we were to doggedly persist with such an approach, we would still have the ugliness of what I feel are the CDS model relationship equivalents of impure functions, that have "side effects", relationships pointing to somewhere outside their scope. I am minded to think about the myriad patch cables that connect different modules on a modular synth, much like the one shown in this classic photo by Jim Gardner, courtesy of Jim and Wikipedia:

.

.

(Yes, that's Steve Porcaro of Toto, keyboard playing brother of Jeff Porcaro, creator of possibly the coolest drum pattern ever, the Rosanna shuffle).

The right way

Staying in the early 80's for a second (Rosanna was from Toto's 1982 album "Toto IV"), we can be mindful of the exhortation taken from the title of Talking Heads' classic studio album from 1980, and "Remain in Light", i.e. adhere to the concept of aspects, rather than tie ourselves up with what is nearer to classes (objects) and relationships.

Reframing the complex object requirement in aspect terms:

aspect ChangeList : {

key ID : UUID;

timestamp : Timestamp;

user : String;

comment : String;

}means that we just need a simpler managed relationship:

extend managed with {

changes : Composition of many ChangeList;and, in Daniel's words (at around 49:33) - "we're done".

Behind the scenes there's still an entity, in the shape of the aspect defined here, but that entity is added by the compiler, as Daniel shows when he pulls back the curtain (via the Preview CDS sources feature in the VS Code extension) to reveal an entity (a "definition") named:

sap.capire.bookshop.Books.changeswhich has a name made up from:

- the namespace

sap.capire.bookshop - the entity name

Books - the element

changes

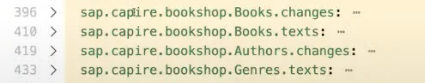

The eagle-eyed amongst you will also have of course spotted the Authors equivalent in that definition list too, as Authors was also adorned with the managed aspect:

In generating this entity, the compiler also includes an element to point back, and because this work is at compile time, and individually specific to each primary entity (Books and Authors here) it can be specific and precise. This is what the YAML representation of the CSN based on the model looks like, for the changes element relating to the Books entity:

sap.capire.bookshop.Books.changes:

kind: entity

elements:

up_:

key: true

type: cds.Association

cardinality: {min: 1, max: 1}

target: sap.capire.bookshop.Books

keys: [{ref: [ID]}]

notNull: true

ID: {key: true, type: cds.UUID}

timestamp: {type: cds.Timestamp}

user: {type: cds.String}

comment: {type: cds.String}This is a lovely example of the truth, the reality, underpinning the general idea that with aspect oriented programming: "you can extend everything that you can get access to, whether it is your definition or somebody else's definition or even your framework's definition". And that extension will be applied to the appropriate usages of that definition.

Daniel goes further to emphasise that while this (deliberately simple) example was in the same schema.cds file, the definitions and extensions can be stored in separate files, used in CDS plugins, and so on. In fact, this is exactly how the Change Tracking Plugin works.

Note that this was a named aspect (the name is ChangeList) but the same modelling outcome could have been effected using an anonymous aspect, like this:

extend managed with {

changes : Composition of many {

key ID : UUID;

timestamp : Timestamp;

user : String;

comment : String;

};

}Wrapping up with relational algebra

CAP's query language, CQL, is based upon and extends SQL in two important directions:

- nested projections

- path expressions (along associations)

From a science perspective, Daniel and the team were keen to validate the idea and realisation of CDS models, and CQL in particular. To this end, behold:

using { sap.capire.bookshop.Books } from './schema';

using { sap.capire.bookshop.Authors } from './schema';

@singleton

entity Schema {

key ID : Integer; // just to make it a valid DDL

Books : Association to many Books on 1=1;

Authors : Association to many Authors on 1=1;

}In case you're scratching your head over

@singleton, Daniel has some advice: "Don't try to look it up, I just invented it" :-)

Consider these queries:

> await cds.ql `SELECT from Schema:Books`

[]then:

> await INSERT({ID:1}).into(Schema)so:

> await cds.ql `SELECT from Schema:Books`

[ (some results) ]Your task (homework), should you choose to accept it, is to think about this, read up on the Relational Model, and maybe even try the queries out yourself.

Until next time!

Update 27 Feb 2025: See the final section of the notes to part 9: Back to the root(s) for more on this and a dig in to making this real.

Footnotes

-

Battle scars.

-

For more on

reduceand how it is such a fundamental building block, see reduce - the ur-function. -

Martin's post Anemic Domain Model is from 2003 and rather cutting but definitely worth a read, as is the Wikipedia article on the same topic.

-

Literally (as many of us use them in our own projects) and technically (as they're supplied in

@sap/cds/common) - see Common Types and Aspects in Capire.

- ← Previous

CAP Node.js plugins - part 3 - writing our own - Next →

TASC Notes - Part 8