TASC Notes - Part 4

These are somewhat more detailed notes than normal that summarise The Art and Science of CAP part 4, one episode in a mini series with Daniel Hutzel to explore the philosophy, the background, the technology history and layers that support and inform the SAP Cloud Application Programming Model.

For all resources related to this series, see the post The Art and Science of CAP.

This episode started with a review of the previous episode (where we collectively decided to make my episode notes into published blog posts like this one).

Functional programming concepts

At around 13:18 Daniel brought up a slide deck from one of my talks on Functional Programming, Functional programming introduction: What, why, how? and the person in the photo on slide four is of course John McCarthy (well done VJ), father of Lisp.

In this context we also touched on currying (which incidentally is named after Haskell Curry, after whom the pure FP language Haskell is also named) and partial application, and then on the concept of a closure - a beautiful technique for implementing lexically scoped name bindings in a language that has support for first class functions (such as JavaScript!).

Everything is a service

At around 17:40 Daniel then turned to the Getting Started area of Capire, and in particular the Services section of the Best Practices topic, where he turns around "When all you have is a hammer, every (thing) is a nail" into "Everything (in CAP) is a service".

In contrast to the "hammer and nail" adage, this axiom is something positive here, something which follows the pattern of uniformity and the elevation of abstraction, in that via CAP's adoption of Hexagonal Architecture the heavy lifting done by the adapters is hidden and of little importance to the application or service developer ... except that (as we see later) that developer can interact with and extend the database connection mechanism as easily and as readily as with their own domain services.

In digging into this, and thinking about lower level facilities abstracted upwards as services, and binding in the related idea (captured in Part 2) that "everything is an event", Daniel made this statement:

"The sum of all your event handlers registered with the service ... is your implementation."

That goes for both local and remote events as well as local and remote services, plus built-in services ... such as a database service, as illustrated in Capire's Extensible Framework section:

cds.db .before ('*', req => {

console.log (req.event, req.target.name)

})and also the Calesi services. And this approach allows us as developers ... to "not care". In the best possible way.

This thinking, this approach, is inspired by Smalltalk's concept of "messaging", in that objects send and receive messages, and of course the receipt of a message is ... an event (upon which event-handling code - which we can think of as an indirect method - is executed).

Daniel goes on to explain Smalltalk's #doesNotUnderstand mechanism which can be effectively turned into a proxy for other services. This idiom is also present in other languages, for example Ruby, in the form of the method_missing construct1.

The REPL

At around 27:00 Daniel opens the REPL, and explains how the set of built-in REPL commands (that begin with a period):

Type ".help" for more information.

> .help

.break Sometimes you get stuck, this gets you out

.clear Alias for .break

.editor Enter editor mode

.exit Exit the REPL

.help Print this help message

.load Load JS from a file into the REPL session

.save Save all evaluated commands in this REPL session to a filecan be extended.

With the REPL started via cds repl we also have CAP specific commands .inspect and .run:

Welcome to cds repl v 8.5.1

> .help

.break Sometimes you get stuck, this gets you out

.clear Alias for .break

.editor Enter editor mode

.exit Exit the REPL

.help Print this help message

.inspect Sets options for util.inspect, e.g. `.inspect .depth=1`.

.load Load JS from a file into the REPL session

.run Runs a cds server from a given CAP project folder, or module name like @capire/bookshop.

.save Save all evaluated commands in this REPL session to a fileWe'll come back to .inspect and .run later.

Lazy loading of the cds facade's many features

In highlighting that the cds object is also available in the REPL, Daniel takes the opportunity to show how the cds object -- as a front-door facade to everything in the runtime that you might need -- is implemented (in @sap/cds/lib/index.js). Not only are super getters involved, but also the general "lazy loading" effect of those getters is used to great effect - a more rapid startup of the server.

Here's a basic example of that lazy loading, based on a simple object definition that looks like this:

const thing = {

name: "Life",

get number() { console.log("in getter"); return 42; }

} In the illustration below, look at the results of each of the REPL's eager evaluations (the values that the REPL shows even before you press Enter):

- the object itself is shown as

{ name: 'Life', number: [Getter]} - the value of the

nameproperty is immediately available (Life) - the value of

numberis not yet available (we are just shown[Getter]) number's value is only resolved when explicitly requested - only then does it cause the function to be executed

As the MDN docu for get states: "The get syntax binds an object property to a function that will be called when that property is looked up. It can also be used in classes" (emphasis mine).

I mentioned in passing this was like a thunk, which is similar, in that it is a mechanism "primarily used to delay a calculation until its result is needed", the concept of which goes back to ALGOL 60.

More on the REPL

Daniel demonstrated the getter-powered lazy loading effect with the cds object, by requesting the env property, which is lazily defined in @sap/cds/lib/index.js2 like this:

get env() { return super.env = require('./env/cds-env').for('cds',this.root) }This caused the inspected cds object to "grow" with the just-evaluated env property.

The .inspect command

And at 31:32 this is where the cds repl's .inspect command comes in, as it allows you to limit the depth to which nested objects will be displayed. Incidentally, if you take a look at the source code for the .inspect command, you'll see a strong FP influence with the use of head and tail, the yin-yang pair of building blocks of recursion and list machinery. And while you're looking at that source code (in @sap/cds-dk/bin/repl.js), note that the default inspect depth ... is also a Schnapszahl:

inspect.defaultOptions.depth = 11The .run command

A minute later at 32:32 Daniel then moved on to demonstrate the other additional command, .run, which uses cds.test() behind the scenes. It is "cap-monorepo-aware" in that one can reference services in subdirectories, like this:

.run cap/samples/bookshopand this will start a CAP server up pretty much in the same way as we're used to with cds watch for example.

If you want to follow along with this exploration, see the Appendix - setting up a test environment.

What's more, though, is that it will also automatically expose REPL-global values representing important aspects of your service and the services upon which it relies:

from cds.entities: {

Books,

Authors,

Genres,

}

from cds.services: {

db,

AdminService,

CatalogService,

UserService,

}

Simply type e.g. Books or db in the prompt to use the respective objects.These values can be combined, as Daniel showed, like this:

> CatalogService.read(Books)

Query {

SELECT: { from: { ref: [ 'sap.capire.bookshop.Books' ] } }

}This example produces a query, which is a first class citizen (taking direction again from FP, just in this case we're dealing with queries, not functions) that can be stored:

> q = CatalogService.read(Books)

Query {

SELECT: { from: { ref: [ 'sap.capire.bookshop.Books' ] } }

}modified:

> q.where({ID:201})

Query {

SELECT: {

from: { ref: [ 'sap.capire.bookshop.Books' ] },

where: [ { ref: [ 'ID' ] }, '=', { val: 201 } ]

}

}

and (eventually) executed, via await, which executes cds.run:

> await q

[

{

createdAt: '2024-12-10T17:26:39.236Z',

createdBy: 'anonymous',

modifiedAt: '2024-12-10T17:26:39.236Z',

modifiedBy: 'anonymous',

ID: 201,

title: 'Wuthering Heights',

descr: `Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë's only novel, was published in 1847 under the pseudonym "Ellis Bell". It was written between October 1845 and June 1846. Wuthering Heights and Anne Brontë's Agnes Grey were accepted by publisher Thomas Newby before the success of their sister Charlotte's novel Jane Eyre. After Emily's death, Charlotte edited the manuscript of Wuthering Heights and arranged for the edited version to be published as a posthumous second edition in 1850.`,

author_ID: 101,

genre_ID: 11,

stock: 12,

price: 11.11,

currency_code: 'GBP'

}

]But - await q - how did that even work?! Perhaps a topic for another post? Let me know.

Interacting with the database service

At around 37:10, going back to the "everything is a service" axiom, Daniel demonstrated that the database connection is indeed a service, and can be extended and manipulated just like any other service, as discussed before. How? Well, for example, by injecting a handler, like this:

cds.db.before('*', console.log)This is very similar to the example in the earlier part of this post; what's interesting here is the use of the raw reference to console.log. Why does that work, and why is it interesting?

Well, it's interesting because it is another neat example of how JavaScript elevates functions to the same level as other values, values that can be stored and even passed as arguments into, or received as output from, other functions. It works because what's expected in this parameter position to a before call is indeed a function; the previous example looks like this:

cds.db .before ('*', req => {

console.log (req.event, req.target.name)

})and the actual call to console.log was inside the body of a lambda1, an anonymous function definition, defined here using the ES6 fat arrow syntax3:

req => { console.log (req.event, req.target.name) }Same type of value - a function.

As a brief aside, note that the first example here was cds.db.before(), typed manually and in a hurry into the REPL, which differs from cds.db .before() in the example from the documentation shown earlier only in syntatic (or is that perhaps "literate"?) whitespace that Daniel likes to sprinkle on his code to make it read more like a human language. Different again is this: db.before(), possible because of the REPL-global names set up by the .run command we saw earlier.

The core of the CAP framework

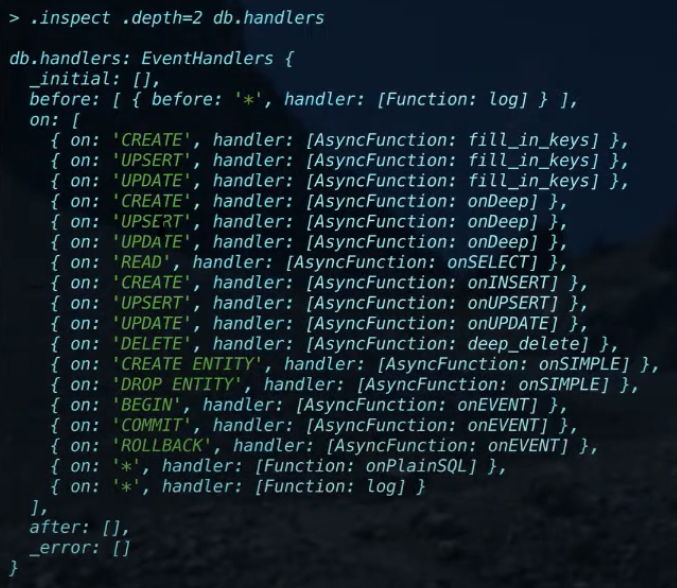

At around 38:38 Daniel use .inspect to look at the handlers - the event handlers - for the db service:

which show the logging function just registered, plus framework handlers for standard persistence layer operations.

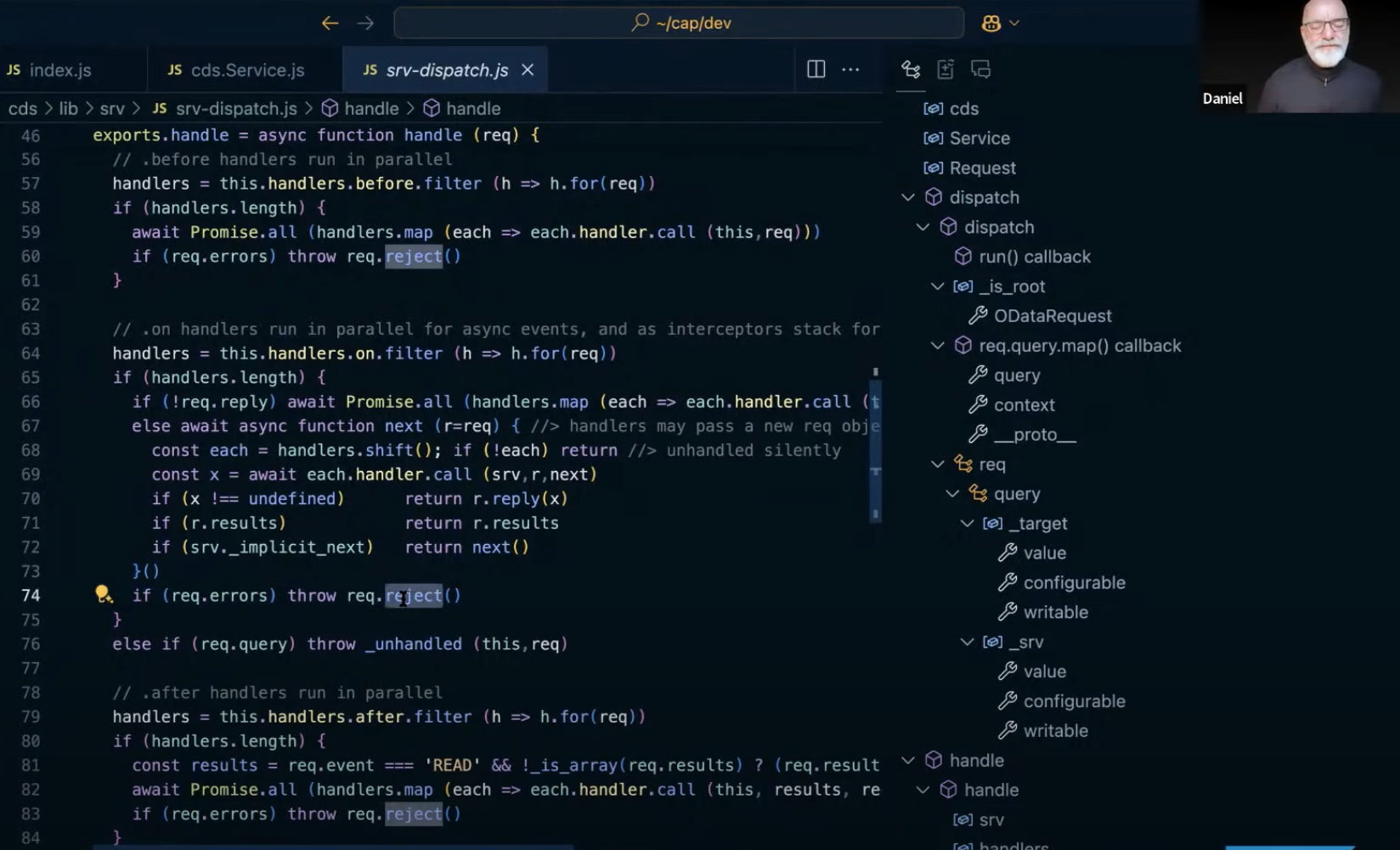

This then led to the uncovering of the effective core of the framework, in @sap/cds/lib/srv.Service.js (which I'm sure some of you may recognise, having debugged through this when working with our own handlers and when & how they're called):

Back to the future

Shortly after this, around 44:15, Daniel switches to Capire's What is CAP? section and points out the anonymous quote:

"CAP is like ABAP for the non-ABAP world"

which causes both Daniel and me to reminisce and indulge in a bit of (well deserved) heavy praise for ABAP and the supporting cast of components and infrastructure, which of course includes:

- the logical databases and corresponding database read programs that formed the framework and support for the early versions of ABAP as a report writing language (

GET KNA1anyone?) in R/2 - the architecture of R/3's disp+work process tree with the different work process role types4 (including the "Verbucher", or "Update Task"), and also how things were structured inside each work process (with the TSKH task handler, DYNP dynpro processor and ABAP language processor)

More philosophising brought us on to the topic of low-code computing, where Daniel mentioned that he'd heard someone claim that the best end-user development tool ... was Excel (which, incidentally, I would posit as a predominantly event oriented programming platform too). Talking of Excel, if you are a fan of the annual December programming competition Advent of Code, then you might want to check out some of the solutions ... written in Excel!

The magic is that there is no magic

At around 47:50 Daniel demonstrates another example of how the REPL allows us to explore CAP as close to the inside of the framework as we can, and improve our understanding of how it really ticks. And, as Daniel said, "fasten your seatbelts!". Here's what happened2.

First, Daniel created a service5, following the simplest thing that could possibly work approach, i.e. what was produced was "just an event handler registry":

> (srv = new cds.Service)

Service {

_handlers: { _initial: [], before: [], on: [], after: [], _error: [] },

name: 'Service',

options: {}

}Then, he sent a simple request initially synchronously, receiving a Promise:

> srv.send('foo',{bar:11})

Promise {

<pending>,

[Symbol(async_id_symbol)]: 53,

[Symbol(trigger_async_id_symbol)]: 6

}To have such a Promise resolved, Daniel then of course did the same thing but in the context of an await, and got ... nothing (well, technically, just no output):

> await srv.send('foo',{bar:11})

>Why? Because the server doesn't have a handler for the foo event that is being sent.

So he defines one:

> srv.on('foo', console.log)

Service {

_handlers: {

_initial: [],

before: [],

on: [ EventHandler { on: 'foo', handler: [Function: log] } ],

after: [],

_error: []

},

name: 'Service',

options: {}

}Looking at what is emitted as output from this call to srv.on here, note how this event handler is indeed registered (this is the "event registry" after all) in the on property. Note also that the same simple technique as earlier is being used here for simplicity: a reference to the function console.log as the argument to the handler parameter.

Making the call again now causes that registered handler to be invoked:

> await srv.send('foo',{bar:11})

Request { method: 'foo', data: { bar: 11 } } [AsyncFunction: next]

>This Request is essentially -- and actually -- an event message!

But perhaps the biggest takeaway from this REPL demo is that what Daniel, Capire and the team is saying about CAP being all about events and services, uniform and abstract, is not only true, but also free of any real complexity underneath. The basic mechanism of the framework is simple and straightforward. There's no magic, it's just events, registries and handlers all the way down.

Tight loops, design time affordances and service integration

Some of CAP's driving principles -- with developers in focus -- are described in Capire's Jumpstart & Grow As You Go... section. The nirvana of a fast inner development loop is achieved through various design time affordances, one of which Daniel demonstrated at around 49:15: the automatic mocking of external services when required.

Using the cloud-cap-samples repo again, Daniel started the "Bookstore" (with cds w bookstore) and the CAP server output included these lines:

[cds] - connect using bindings from: { registry: '~/.cds-services.json }

[cds] - connect to db > sqlite { url: ':memory:' }

[cds] - connect to messaging > file-based-messaging

[cds] - using new OData adapter

[cds] - mocking ReviewsService { impl: 'reviews/srv/reviews-service.js', path: '/reviews' }

[cds] - mocking OrdersService { impl: 'orders/srv/orders-service.js', path: '/odata/v4/orders' }

[cds] - serving CatalogService { impl: 'bookshop/srv/cat-service.js', path: '/browse' }

[cds] - serving AdminService { impl: 'bookshop/srv/admin-service.js', path: '/admin' }

[cds] - serving UserService { impl: 'bookshop/srv/user-service.js', path: '/user' }

[cds] - serving DataService { impl: 'data-viewer/srv/data-service.js', path: '/odata/v4/-data' }The "Bookstore" app uses the "Reviews" Service as shown in the diagram:

and as defined in cloud-cap-samples/bookstore/srv/mashup.cds:

using { ReviewsService.Reviews } from '@capire/reviews';And because at this point the "Reviews" service isn't running, and (more importantly) there isn't a service binding for any such remote service, the CAP server will automatically mock it.

What gives us a glimpse under the hood of this mechanism is when Daniel actually starts the "Reviews" service too, in a separate window, with cds w reviews, whereupon we see these lines in that second CAP server's output:

[cds] - serving ReviewsService { impl: 'reviews/srv/reviews-service.js', path: '/reviews' }

[cds] - server listening on { url: 'http://localhost:4005' }But more importantly, we can see that when the "Bookstore" is restarted, the "Reviews" service is no longer mocked, because now a service binding for it was found, in the context of Daniel's development environment.

The result is that instead of this line appearing in the "Bookstore" CAP server log output:

[cds] - mocking ReviewsService { impl: 'reviews/srv/reviews-service.js', path: '/reviews' }what we get now is this:

[cds] - connect to ReviewsService > odata { url: 'http://localhost:4005/reviews' }How does this design time binding machinery management work? Well, it's based on a developer-local configuration file that the CAP server(s) share. And if we look carefully at the original log output from the "Bookstore" CAP server, we see this line, which tells us what that file is called and where it is:

[cds] - connect using bindings from: { registry: '~/.cds-services.json }When a CAP server starts up, in design time mode (e.g. via cds watch), it writes binding information for services that it provides, into this ~/.cds-services.json file. And when a CAP server starts up and knows it needs a connection to a remote service, via a service binding, and is also in design time mode, it will look in this same file to see what is being provided already, and use that information if it exists.

Such a simple concept, beautifully executed.

If you're curious, this is the sort of information that is stored, for running CAP services in design time mode, in the ~/.cds-services.json file:

{

"cds": {

"provides": {

"ReviewsService": {

"kind": "odata",

"credentials": {

"url": "http://localhost:4005/reviews"

}

}

}

}

}This section was written to ~/.cds-services.json by the second CAP server where the "Reviews" services was started up. Note the provides property pointing to the CAP server URL6. And it's read by the first CAP server looking for (design time) service binding information for that service.

Service integration CodeJam

If you are looking to learn "more than you ever wanted to know" about service integration, including more details on this wonderful mechanism, you might want to organise or attend the Service Integration with CAP CodeJam, or if you can't make an in-person event, you can still look through the entire CodeJam content, which is all available online.

That wraps it up for the notes on this part 4, I hope you enjoyed them, and see you online!

Footnotes

- This Ruby idiom is a form of metaprogramming, which was popularised with Lisp ... which brings us back to McCarthy. Moreover, as Sinclair Target mentioned in his great article How Lisp Became God's Own Programming Language (which is also available in audio format as an episode on my Tech Aloud podcast), "Ruby is also a Lisp", expounded upon by Eric Kidd in his post Why Ruby is an acceptable LISP.

Eric's post incidentally also shows how functions can be first class citizens, and even goes on to give a great example of a closure - the accumulator function, which in turn is from the appendix of Paul Graham's Revenge of the Nerds post. Here's the original accumulator function definition (named foo here) in Lisp:

(defun foo (n) (lambda (i) (incf n i)))and here is how we might express it in JavaScript:

foo = n => i => n += iBoth implementations illustrate the concept of functions as first class citizens (the anonymous function i => n += i is returned as a value from a call to the named function foo) as well as the concept of a closure (n is "closed over", and therefore "captured", in the construct, and lives on inside that anonymous function). Here's a Node.js REPL session showing an example of use:

Welcome to Node.js v22.6.0.

Type ".help" for more information.

> foo = n => i => n += i

[Function: foo]

> mysum = foo(10)

[Function (anonymous)]

> mysum(2)

12

> mysum(3)

15

>Note also that the word "lambda", used here specifically and syntactically in Lisp as the symbol for an anonymous function, has become the de facto term for anonymous functions in general - for example, Python uses the term, and AWS has a Functions-as-a-Service (FaaS) offering called Lambda.

For an indication of how fundamental the concept of first class functions is (along with the closely related "higher order" function style), see Functions as first class citizens in SICP Lecture 1A.

2. Examples in this post are based on CAP Node.js version 8.5.1 (Nov 2024) rather than the 8.6.0 version that Daniel had, which is currently not available externally at the time of writing.

3. Properly called Arrow function expressions.

4. DVEBMGS00 anyone? (The V here is for "Verbucher" of course) :-)

5. I suspect that the only reason srv = new cds.Service was wrapped in parentheses here was because Daniel had originally intended to immediately send something to the newly created server (but still capture a reference to that server), i.e. like this: (srv = new cds.Service).send('foo',{bar:11}) but had then decided to break it down into individual steps.

6. No further credential information exists here, as it's a design time only service running locally.

Appendix - setting up a test environment

If you want to set up a test environment exactly like the one used for this post, specifically the REPL illustrations, then you can. I do most things in containers, and I have different container images representing CAP Node.js at different versions. For the illustration in this blog post I am using CDS 8.5.1 with Node.js major version 22.

First, download the CAP image builder, build the base image and an 8.5.1 specific version:

git clone https://github.com/qmacro/cap-con-img && cd cap-con-img

./buildbase && ./buildver 8.5.1Now start up a temporary container based on that image:

docker run --rm -it cap-8.5.1 bashThis will give you a Bash shell prompt:

node ➜ ~

$Now, in that shell, you can clone the cloud-cap-samples repo to enjoy the structured set of services:

git clone https://github.com/SAP-samples/cloud-cap-samples \

&& cd cloud-cap-samplesAfter installing the dependencies:

npm installyou can start the REPL:

cds replwhich will give you the prompt you're looking for:

Welcome to cds repl v 8.5.1

>where you can start to experiment with:

.run bookshopwhich will produce something like this:

[cds] - loaded model from 5 file(s):

bookshop/srv/user-service.cds

bookshop/srv/cat-service.cds

bookshop/srv/admin-service.cds

bookshop/db/schema.cds

node_modules/@sap/cds/common.cds

[cds] - connect to db > sqlite { url: ':memory:' }

> init from bookshop/db/init.js

> init from bookshop/db/data/sap.capire.bookshop-Genres.csv

> init from bookshop/db/data/sap.capire.bookshop-Books.texts.csv

> init from bookshop/db/data/sap.capire.bookshop-Books.csv

> init from bookshop/db/data/sap.capire.bookshop-Authors.csv

/> successfully deployed to in-memory database.

[cds] - using auth strategy {

kind: 'mocked',

impl: 'node_modules/@sap/cds/lib/srv/middlewares/auth/basic-auth'

}

[cds] - using new OData adapter

[cds] - serving AdminService { impl: 'bookshop/srv/admin-service.js', path: '/admin' }

[cds] - serving CatalogService { impl: 'bookshop/srv/cat-service.js', path: '/browse' }

[cds] - serving UserService { impl: 'bookshop/srv/user-service.js', path: '/user' }

[cds] - server listening on { url: 'http://localhost:46025' }

[cds] - launched at 12/10/2024, 5:26:38 PM, version: 8.5.0, in: 887.147ms

[cds] - [ terminate with ^C ]

------------------------------------------------------------

Following are made available as repl globals:

from cds.entities: {

Books,

Authors,

Genres,

}

from cds.services: {

db,

AdminService,

CatalogService,

UserService,

}

Simply type e.g. Books or db in the prompt to use the respective objects.

>whereupon you're ready to explore as we do in this post.