Monday morning thoughts: OData

In this post, I think about OData, in particular where it came from and why it looks and acts like it does. I also consider why I think it was a good protocol for an organisation like SAP to embrace.

🔊 This post is also available in audio format on the Tech Aloud podcast.

OData. Or as some people write it (which causes me to gnash my teeth) "oData". Not as bad as "O'Data" as Brenton O'Callaghan writes it, just to annoy me, though. Anyway, on a more serious note, I've been thinking about OData recently in the context of the fully formed and extensible CRUD+Q server that you can get for free with a small incantation of what seems to be magic in the form of the tools of the Application Programming Model for SAP Cloud Platform. I was also thinking about OData because of Holger Bruchelt's recent post Beauty of OData - nice one Holger.

OData fundamentals

OData is a protocol and a set of formats. It is strongly resource oriented, as opposed to service oriented, which to me as a fan of simplicity and RESTfulness is a very good thing. Consider Representational State Transfer (REST) as an architectural style, which it is, rather than a specific protocol (which it isn't), and you'll come across various design features that this style encompasses. For me, though, the key feature is the uniform interface - there are a small fixed number of verbs (OData operations) and an infinite set of nouns (resources) upon which the verbs operate. These OData operations map quite cleanly onto the HTTP methods that we know & love, and understand at a semantic level:

| OData operation | HTTP method |

|---|---|

| C - Create | POST |

| R - Read | GET |

| U - Update | PUT |

| D - Delete | DELETE |

| Q - Query | GET |

There's more to this (e.g. the use of PATCH for merge semantics, or the batching of multiple operations within an HTTP POST request) but basically that's it. We have a standard set of CRUD+Q operations that cover the majority of use cases when thinking about the manipulation of resources. And for the edge cases where thinking in terms of resources and relationships between them would be too cumbersome, there's the function import mechanism (with which I have a love-hate relationship, as it's useful but also rather service oriented and therefore opaque).

Beyond the protocol itself, there's the the shape of the data upon which the OData operations are carried out. I don't mean the format - that's separate, and multi-faceted too. OData formats, which relates to the RESTful idea of multiple possible representations of a resource, come in different flavours - predominantly XML and JSON based. What I mean with "shape" is how the data in OData resources is represented.

One of the things I used to say a lot was that if something was important enough it should be addressable. More particularly, business data should be addressable in that elements should have addresses, not hidden behind some sort of opaque web services endpoint. In the case of an HTTP protocol like OData, these addresses are URLs. And the shape of the data can be seen in the way those URL addresses are made up*.

*some absolute RESTful purists might argue that URLs should be opaque, that we should not imply meaning from their structure. That to me is a valid but extreme position, and there has to be a balance between the beautiful theory of absolute purity and the wonderful utility of real life pragmatism.

And the shape of the data, which itself is uniform and predictable, allows this to happen. To understand what this shape is and how it works, I wanted to take a brief look at OData's origins.

OData's origins

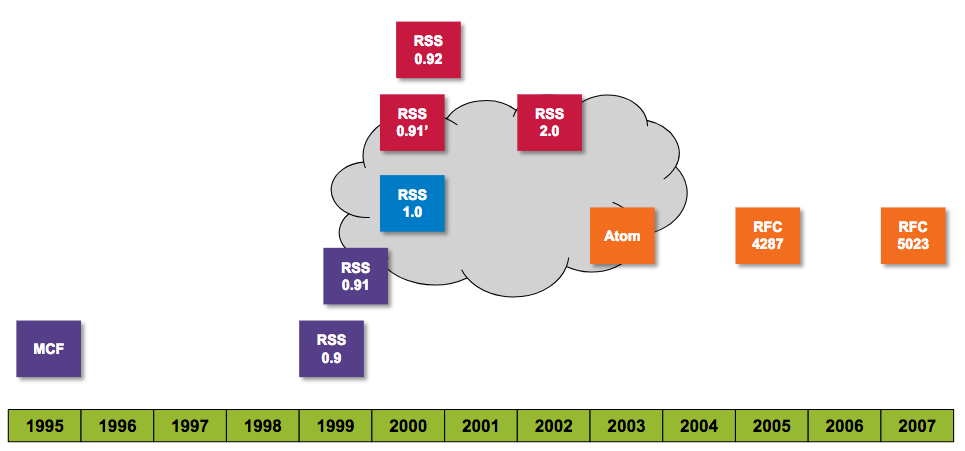

OData goes back further than you might think. Here's an image from a session on OData that I gave a few years ago:

The protohistory of OData

I'd suggest that if one looks at the big picture, OData's origins go back to 1995, with the advent of the Meta Content Framework (MCF). This was a format that was created by Ramanthan V Guha while working in Apple's Advanced Technology Group, and its application was in providing structured metadata about websites and other web-based data, providing a machine-readable version of information that humans dealt with.

A few years later in 1999 Dan Libby worked with Guha at Netscape to produce the first version of a format that many of us still remember and perhaps a good portion of us still use, directly or indirectly - RSS. This first version of RSS built on the ideas of MCF and was specifically designed to be able to describe websites and in particular weblog style content - entries that were published over time, entries that had generally had a timestamp, a title, and some content. RSS was originally written to work with Netscape's "My Netscape Network" - to allow the combination of content from different sources (see Spec: RSS 0.9 (Netscape) for some background). RSS stood then for RDF Site Summary, as it used the Resource Description Framework (RDF) to provide the metadata language itself. (I have been fascinated by RDF over the years, but I'll leave that for another time.)

I'll fast-forward through the period directly following this, as it involved changes to RSS as it suffered at the hands of competing factions, primarily caused by some parties unwilling to cooperate in an open process, and it wasn't particularly an altogether pleasant time (I remember, as I was around, close to the ongoing activities and knew some of the folks involved). But what did come out of this period was the almost inevitable fresh start at a new initiative, called Atom. Like RSS, the key to Atom was the structure with which weblog content was described, and actually the structure was very close indeed to what RSS looked like.

An Atom feed, just like an RSS feed, was made up of some header information describing the weblog in general, and then a series of items representing the weblog posts themselves:

header

item

item

...And like RSS feeds, Atom feeds - also for machine consumption - were made available in XML, in parallel to the HTML-based weblogs themselves, which of course were for human consumption.

A few years later, in 2005, the Atom format became an Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) standard, specifically RFC 4287, and became known as the Atom Syndication Format:

"Atom is an XML-based document format that describes lists of related information known as "feeds". Feeds are composed of a number of items, known as "entries", each with an extensible set of attached metadata. For example, each entry has a title."

And like RSS feeds, Atom feeds - also for machine consumption - were made available in XML, in parallel to the HTML-based weblogs themselves, which of course were for human consumption.

A few years later, in 2005, the Atom format became an Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) standard, specifically RFC 4287, and became known as the Atom Syndication Format:

"Atom is an XML-based document format that describes lists of related information known as "feeds". Feeds are composed of a number of items, known as "entries", each with an extensible set of attached metadata. For example, each entry has a title."

What was magic, though, was that in addition to this format, there was a fledgling protocol that was used to manipulate data described in this format. It was first created to enable remote authoring and maintenance of weblog posts - back in the day some folks liked to draft and publish posts in dedicated weblog clients, which then needed to interact with the server that stored and served the weblogs themselves. This protocol was the Atom Publishing Protocol, "AtomPub" or APP for short, and a couple of years later in 2007 this also became an IETF standard, RFC 5023:

The Atom Publishing Protocol is an application-level protocol for publishing and editing Web Resources using HTTP [RFC2616] and XML 1.0 [REC-xml]. The protocol supports the creation of Web Resources and provides facilities for:

- Collections: Sets of Resources, which can be retrieved in whole or in part.

- Services: Discovery and description of Collections.

- Editing: Creating, editing, and deleting Resources.

Is this starting to sound familiar, OData friends?

Well, yes, of course it is. OData is exactly this - sets of resources, service discovery, and manipulation of individual entries.

AtomPub and the Atom Syndication Format was adopted by Google in its Google Data (GData) APIs Protocol while this IETF formalisation was going on and the publish/subscribe protocol known as PubSubHubbub (now called WebSub) originally used Atom as a basis. And as we know, Microsoft embraced AtomPub in the year it became an IETF standard and OData was born.

Microsoft released the first three major versions of OData under the Open Specification Promise, and then OData was transferred to the guardianship of the Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information Standards (OASIS) and the rest is history.

Adoption at SAP

I remember an TechEd event quite a few years back (it may have been ten or more) where I had a conversation with a chap at SAP who had been one of the members of a group that had been searching for a data protocol to adopt to take SAP into a new era of interoperability and integration. After a lot of technical research they decided upon OData. It was an open standard, a standard with which they could get involved, alongside Microsoft, IBM and others. For example, in 2014 OData version 4.0 was announced as an OASIS standard.

It was clear to me why such a standard was needed. In the aftermath of the WS-deathstar implosion there was clearly a desire for simplicity, standardisation, openness, interoperability and perhaps above all (at least in my view) a need for something that humans could understand, as well as machines. The resource orientation approach has a combination of simplicity, power, utility and beauty that is reflected in (or by) the web as a whole. One could argue that the World Wide Web is the best example of a hugely distributed web service, but that's a discussion for another time.

OData has constraints that make for consistent and predictable service designs - if you've seen one OData service you've seen them all. And it passes the tyre-kicking test, in that the tyres are there for you to kick - to explore an OData service using read and query operations all you need is your browser.

OData's adoption at SAP is paying off big time. From the consistencies in what we see across various SAP system surfaces, especially in the SAP Cloud Platform environment, through the simple ability to eschew the OData flavour itself and navigate OData resources as simple HTTP resources (how often have I seen UI5 apps retrieving OData resources and plonking the results into a JSON model?) to the crazy (but cool) ability to consume OData from other tools such as Excel. (Why you'd want to use these tools is a complete mystery to me, but that's yet another story for another time, one best told down the pub.)

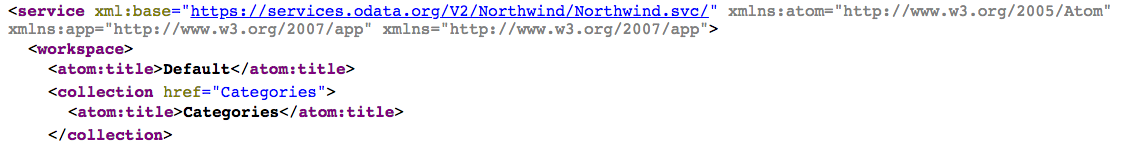

If you do one thing before your next coffee, have a quick look at an OData service. The Northwind service maintained by OASIS will do nicely. Have a look at the service document:

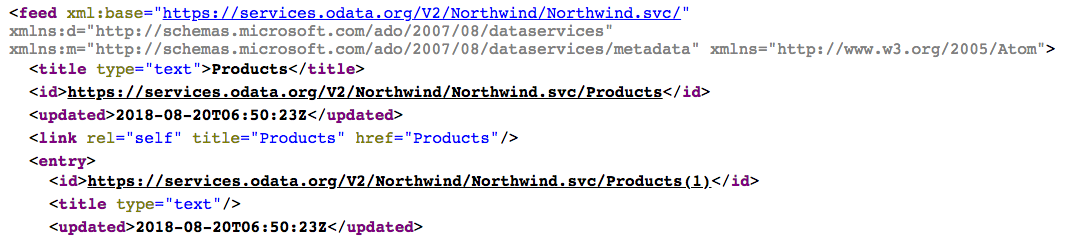

and, say, the Products collection.

Notice how rich and present Atom's ancestry is in OData today. In the service document, entity sets are described as collections, and the Atom standard is referenced directly in the "atom" XML namespace prefix. In the Products entity set, notice that the root XML element is "feed", an Atom construct (we refer to weblog Atom and RSS "feeds") and the product entities are "entry" elements, also a direct Atom construct.

Today's business API interoperability and open standards are built upon a long history of collaboration and invention.

This post was brought to you by Pact Coffee's Planalto and the delivery of the milk by the milkman even earlier than usual.

Read more posts in this series here: Monday morning thoughts.