Running: 2014 in review, and some Clojure

I enjoyed running in 2014 and logged each one via Endomondo. This post is a random collection of thoughts about the running, the data and some simple analysis, in Clojure.

Watches

I’ve been using a Garmin Forerunner 110 watch which has been very good, on the whole, although the USB cable and connectivity left something to be desired.

I bought my wife Michelle a TomTom Runner Cardio for her birthday back in August, and have been intrigued by it ever since. And she bought me one for Christmas, so I’m trying that out for 2015. I went out on my first run of this year with it just this morning, in fact.

Run data

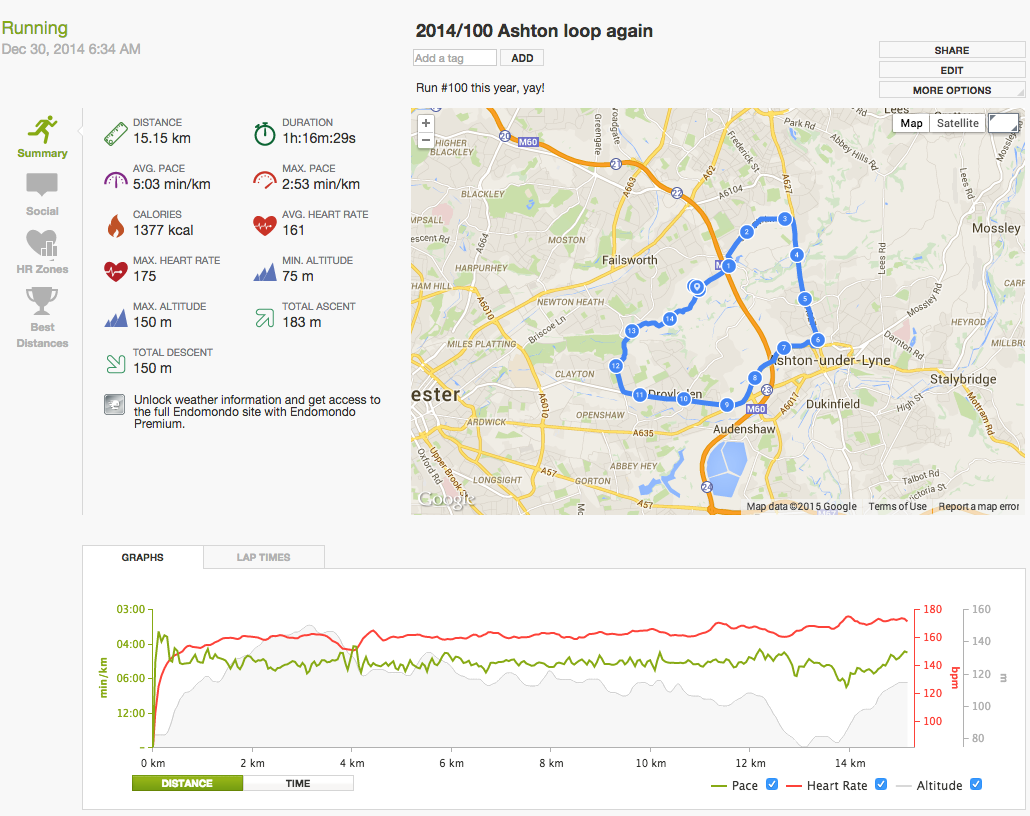

But back to 2014. I completed 101 runs (1,281.22km) and they’re all logged in Endomondo. I don’t have the premium subscription, just the basic, but the features are pretty good. There’s an option to upload from the Garmin watch, via a browser plugin which (on this OSX machine) has become pretty flakey recently and now only works in Safari, but once uploaded, the stats for each run are shown rather nicely:

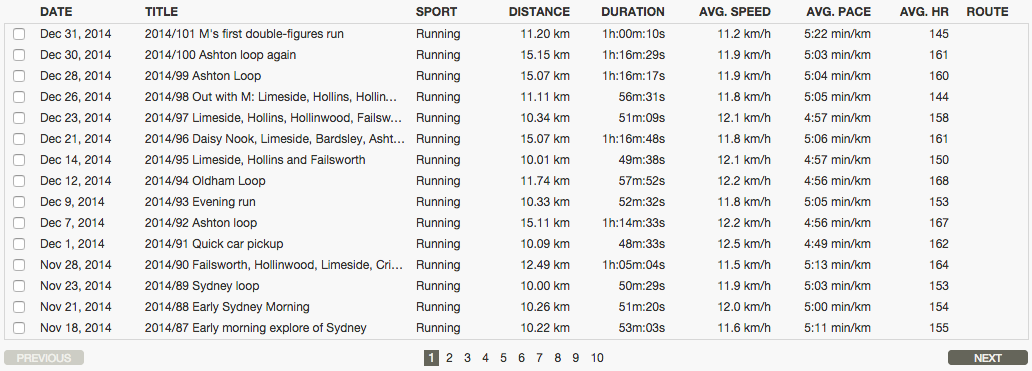

Endomondo also offers simple statistics and charts, and a tabular overview of the runs, that looks like this:

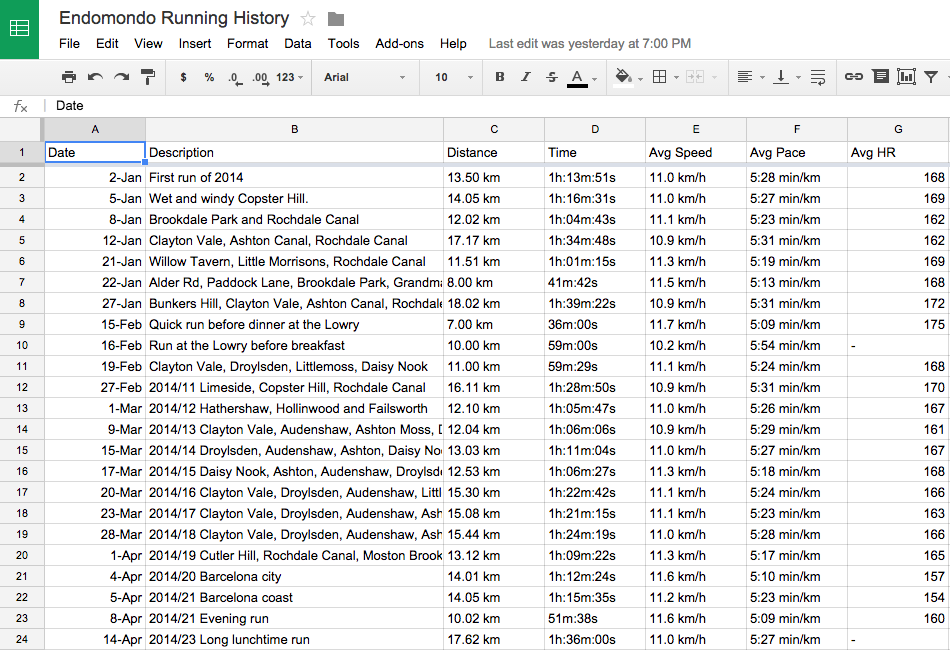

One thing that bothered me, at least with the free service, is that there was no option to download this data. So I paged through the tabular data, and copy/pasted the information into a Google Sheet, my favourite gathering-and-stepping-off point for a lot of my data munging.

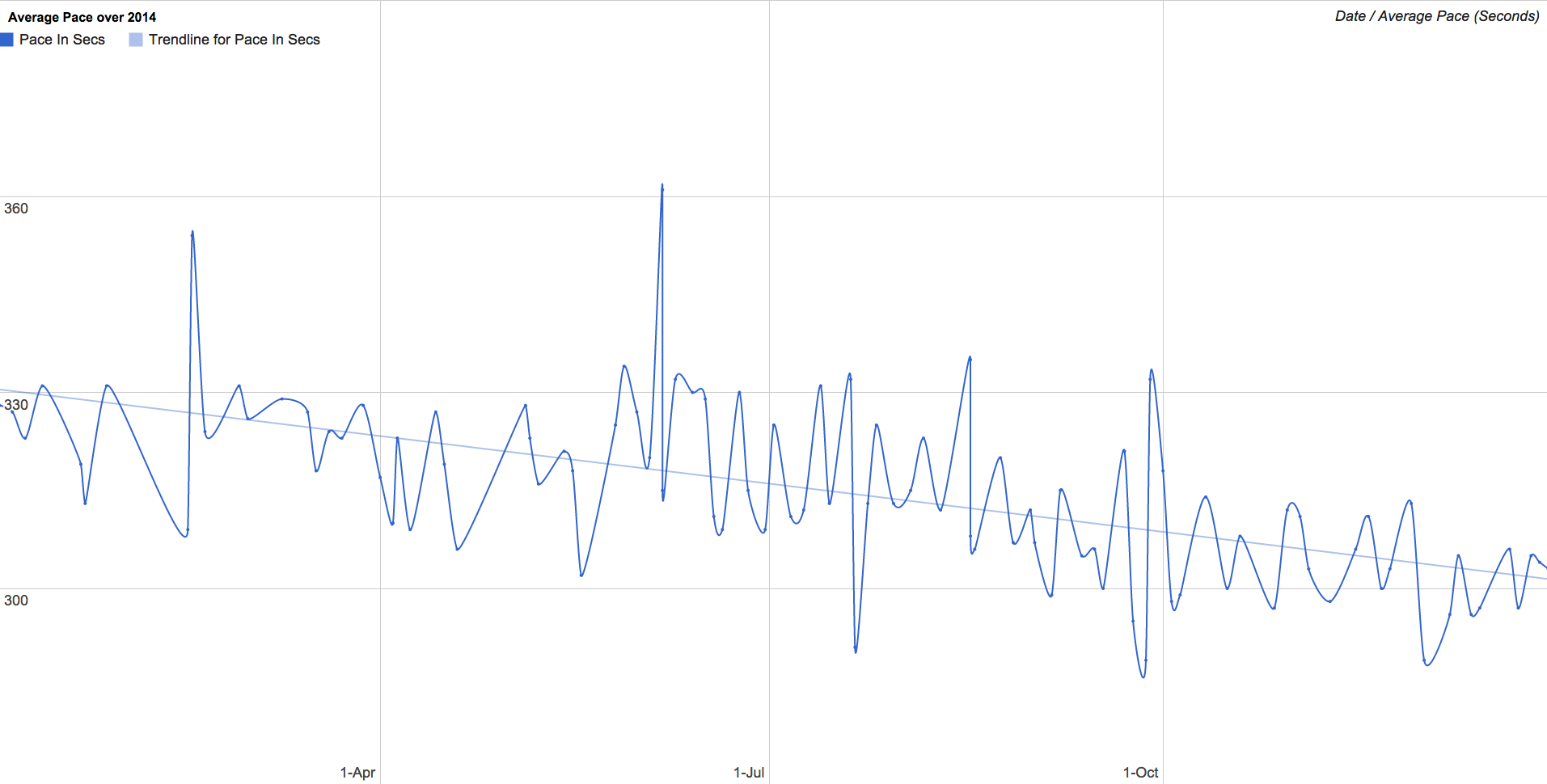

If nothing else, as long as the data is largely two dimensional, I’ve found it’s a good way to visually inspect the data at 10000 feet. It also affords the opportunity for some charting action, so I had a look at my pace over the year, to see how it had improved. This is the result:

The three peaks in Feb, Jun and Sep are a couple of initial runs I did with Michelle plus her first 8km in London (now she’s in double km figures and has a decent pace, I’m very proud of her).

Some Analysis in Clojure

I could have gone further with the analysis in the spreadsheet itself, but I’m also just starting to try and teach myself Clojure, and thought this would be a nice little opportunity for a bit of data retrieval and analysis.

Exposing the data

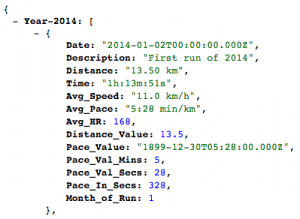

Of course, the first thing to do was to make the data in the Google Sheet available, which I did with my trusty SheetAsJSON mechanism. It returned a nice JSON structure that contained all the data that I needed.

So now I had something that I could get Clojure to retrieve. Here follows some of what I did.

Creating the project

I’m using Leiningen, which is amazing in a combined couple of ways: it Just Works(tm), and it uses Maven. My only previous experience of Maven had me concluding that Maven was an absolute nightmare, but Leiningen has completely changed my mind. Although I don’t actually have to think about Maven at all, Leiningen does it all for me, and my hair is not on fire (for those of you wondering, Leiningen’s tagline is "for automating Clojure projects without setting your hair on fire", which I like).

So I used Leiningen to create a new application project:

lein new app running-statsand used my joint-favourite editor (Vim, obviously, along with Atom), with some super Clojure-related plugins such as vim-fireplace, to edit the core.clj file. (more on my Vim plugins another time).

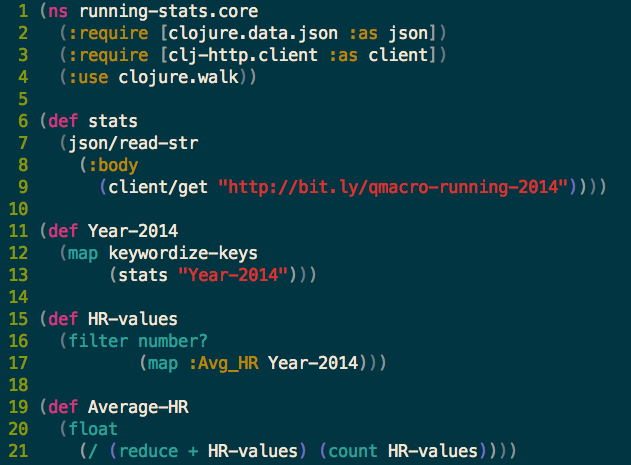

Here’s a short exerpt from what I wrote:

Let’s look at this code step by step.

Library use

I’m using Clojure’s data.json library (line 2) to be able to parse the JSON that my SheetAsJSON mechanism is exposing. I’m also using the clj-http HTTP client library (line 3) to make the GET request. Finally I’m using the clojure.walk library (line 4) for a really useful function later on.

I decided to churn through step by step, which is why you’re seeing this code in four chunks, each time using the def special form to create a var in the current namespace.

Creating stats

There’s stats (line 6), which has the value of the parsed JSON from the body of the response to the HTTP GET request. To unravel lines 6-9 we have to read from the inside outwards.

First, there’s the call to client/get in line 9 (the clj-http library is aliased as client in line 3). This makes the HTTP GET request and the result is a Persistent Array Map that looks something like this:

running-stats.core=> (client/get "http://bit.ly/qmacro-running-2014") {:cookies {"NID" {:discard false, :domain ".googleusercontent.com", :expires #inst "2015-07-05T12:23:49.000-00:00", :path "/", :secure false, :value "67=EUPTfvAv3U5Vofm1F3Fb_D9OjmwYS1yC3Ju-uvgostmqzKSNLHKHiHGMc-cwFBAES0R3qcLFQW7W75x6sZjSzein3H7Trxeg6Bk0wOJ0q-AaYXA0RxYw0-uEhR5ogaXg", :version 0}}, :orig-content-encoding nil, :trace-redirects ["http://bit.ly/qmacro-running-2014" "https://script.googleusercontent.com/macros/echo?user_content_key=jmP [...] 5, :status 200, :headers {"Server" "GSE", "Content-Type" "application/json; charset=utf-8", "Access-Control-Allow-Origin" "*", "X-Content-Type-Options" "nosniff", "X-Frame-Options" "SAMEORIGIN", "Connection" "close", "Pragma" "no-cache", "Alternate-Protocol" "443:quic,p=0.02", "Expires" "Fri, 01 Jan 1990 00:00:00 GMT", "P3P" "CP="This is not a P3P policy! See http://www.google.com/support/accounts/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=151657 for more info."", "Date" "Sat, 03 Jan 2015 12:25:02 GMT", "X-XSS-Protection" "1; mode=block", "Cache-Control" "no-cache, no-store, max-age=0, must-revalidate"}, :body "{"Year-2014":[{"Date":"2014-01-02T00:00:00.000Z","Description":"First run of 2014","Distance":"13.50 km","Time":"1h:13m:51s","Avg_Speed":"11.0 km/h","Avg_Pace":"5:28 min/km","Avg_HR":168,"Distance_Value":13.5,"Pace_Value":"1899-12-30T05:28:00.000Z","Pace_Val_Mins":5,"Pace_Val_Secs":28,"Pace_In_Secs":328,"Month_of_Run":1},{"Date":"2014-01-05T00:00:00.000Z","Description":"Wet and windy Copster Hill.","Distance":"14.05 km","Time":"1h:16m:31s","Avg_Speed":"11.0 km/h","Avg_Pace":"5:27 min/km","Avg_HR":169,"Distance_Value":14.05,"Pace_Value":"1899-12-30T05:27:00.000Z","Pace_Val_Mins":5,"Pace_Val_Secs":27,"Pace_In_Secs":327,"Month_of_Run":1},{"Date":"2014-01-08T00:00:00.000Z","Description":"Brookdal [...]

Quite a bit of a result. Looking at the keys of the map, we see the following, which should be somewhat familiar to anyone who has made HTTP calls:

running-stats.core=> (keys (client/get "http://bit.ly/qmacro-running-2014")) (:cookies :orig-content-encoding :trace-redirects :request-time :status :headers :body)

There we can see the :body keyword, which we use on line 8 as an accessor in this collection. With this, we get the raw body, a string, representing the JSON:

running-stats.core=> (:body (client/get "http://bit.ly/qmacro-running-2014")) "{"Year-2014":[{"Date":"2014-01-02T00:00:00.000Z","Description":"First run of 2014","Distance":"13.50 km","Time":"1h:13m:51s","Avg_Speed":"11.0 km/h","Avg_Pace":"5:28 min/km","Avg_HR":168,"Distance_Value":13.5,"Pace_Value":"1899-12-30T05:28:00.000Z","Pace_Val_Mins":5,"Pace_Val_Secs":28,"Pace_In_Secs":328,"Month_of_Run":1},{"Dat [...]

Now we need to parse this JSON with the data.json library, which we do in line 7. This gives us something like this:

running-stats.core=> (json/read-str (:body (client/get "http://bit.ly/qmacro-running-2014"))) {"Year-2014" [{"Pace_Val_Secs" 28, "Distance_Value" 13.5, "Date" "2014-01-02T00:00:00.000Z", "Month_of_Run" 1, "Description" "First run of 2014", "Distance" "13.50 km", "Avg_Speed" "11.0 km/h", "Pace_Val_Mins" 5, "Pace_Value" "1899-12-30T05:28:00.000Z", "Avg_Pace" "5:28 min/km", "Time" "1h:13m:51s", "Pace_In_Secs" 328, "Avg_HR" 168} {"Pace_Val_Secs" 27, "Distance_Value" 14.05, "Date" "2014-01-05T00:00:00.000Z", "Month_of_Run" 1, "Description" "Wet and windy Cop [...]

which is eminently more useable as it’s another map.

Although it’s a map, the keys are strings which aren’t ideal if we want to take advantage of some Clojure idioms. I may be wrong here, but I found that converting the keys into keywords made things simpler and felt more natural, as you’ll see shortly.

The Year-2014 data set

Lines 11-13 is where we create the Year-2014 var, representing the data set in the main spreadsheet tab.

Looking up the “Year-2014″ key in the stats (line 13) gave me a vector, signified by the opening square bracket:

running-stats.core=> (stats "Year-2014") [{"Pace_Val_Secs" 28, "Distance_Value" 13.5, "Date" "2014-01-02T00:00:00.000Z", "Month_of_Run" 1, "Description" "First run of 2014", "Distance" "13.50 km", "Avg_Speed" "11.0 km/h", "Pace_Val_Mins" 5, "Pace_Value" "1899-12-30T05:28:00.000Z", "Avg_Pace" "5:28 min/km", "Time" "1h:13m:51s", "Pace_In_Secs" 328, "Avg_HR" 168} {"Pace_Val_Secs" 27, "Distance_Value" 14.05, "Date" "2014-01-05T00:00:00.000Z", "Month_of_Run" 1, "Description" "Wet and windy Copster Hill.",

The vector contained maps, one for each run. Each map had strings as keys, so in line 12 I used the keywordize-keys function, from clojure.walk, to transform the strings to keywords. Here’s an example, calling the function on the map representing the first run in the vector:

running-stats.core=> (keywordize-keys (first (stats "Year-2014"))) {:Pace_Value "1899-12-30T05:28:00.000Z", :Month_of_Run 1, :Distance_Value 13.5, :Distance "13.50 km", :Avg_HR 168, :Avg_Pace "5:28 min/km", :Pace_Val_Mins 5, :Pace_Val_Secs 28, :Date "2014-01-02T00:00:00.000Z", :Description "First run of 2014", :Time "1h:13m:51s", :Avg_Speed "11.0 km/h", :Pace_In_Secs 328}

I assigned the resulting value of this call to a new var Year-2014.

Getting the HR values

The Garmin Forerunner 110 measures heart rate (HR) via a chest strap, and an average-HR detail is available for each run:

running-stats.core=> (:Avg_HR (first Year-2014)) 168

There were a few runs where I didn’t wear the chest strap, so the value for this detail on those runs was a dash, rather than a number, in the running statistics on the Endomondo website, which found its way into the spreadsheet and the JSON.

running-stats.core=> (count (filter (comp not number?) (map :Avg_HR Year-2014))) 6

Yes, six runs altogether without an average HR value. So to get the real average HR values, I just needed the ones that were numbers. I did this on lines 15-17.

By the way, composing with the comp function sort of makes me go “wow”, because I figure this is revealing a bit of the simplicity, depth and philosophy that lies beneath the scratch mark I’ve just made in the surface of functional programming in general and Clojure in particular.

Average HR

I took the average of the HR values in line 21. This actually returned a Ratio type:

running-stats.core=> (/ (reduce + HR-values) (count HR-values)) 15292/95 running-stats.core=> (type (/ (reduce + HR-values) (count HR-values))) clojure.lang.Ratio

This was interesting in itself, but I wanted a value that told me something, so I called the float function in line 20:

running-stats.core=> (float (/ (reduce + HR-values) (count HR-values))) 160.96841

(Yes, I know taking the average of averages is not a great thing to do, but at this stage I’m more interested in my Clojure learning than my running HR in 2014).

And more

I did continue with my analysis in Clojure, but this post is already long enough, so I’ll leave it there for now. If you got this far, thanks for reading! I hope to teach myself more Clojure; there are some great resources online, and the community is second to none.

If you’re thinking of taking the plunge, I’d recommend it! I’ll leave you with a quote from David Nolen at the end of his talk “Jelly Stains. Thoughts on JavaScript, Lisp and Play” at JSConf 2012:

“[Dan Friedman and William Byrd] got me realising there’s a lot more left to play with in Computer Science”.

As I embark upon my journey in this direction, I realise that’s a very true statement. It’s like learning programming all over again, in a good way!