Functions as first class citizens in SICP Lecture 1A

In my notes on part 4 of The Art and Science of CAP I make a number of references to functions as first class citizens, and show the parallel with queries also in CAP having that same first class citizenship. Both can be assigned to variables, passed around, and provided as input, and even received as output, to function calls.

I am re-visiting the classic MIT Course 6.001, called "The Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs", also called simply "SICP". Not only is a PDF of the second edition of the book available, but also a series of course lecture recordings from 1986 - old, and not of the highest audio or visual quality, but priceless.

And do you know what? While to some the idea of first class citizenship for functions is still an unknown concept or not even something they've thought of (due perhaps mainly to the constraints or design of the languages they have used), and to others it's part of some "higher order" thinking that is impractical or unimportant ... this concept is introduced in the very first lecture of this course.

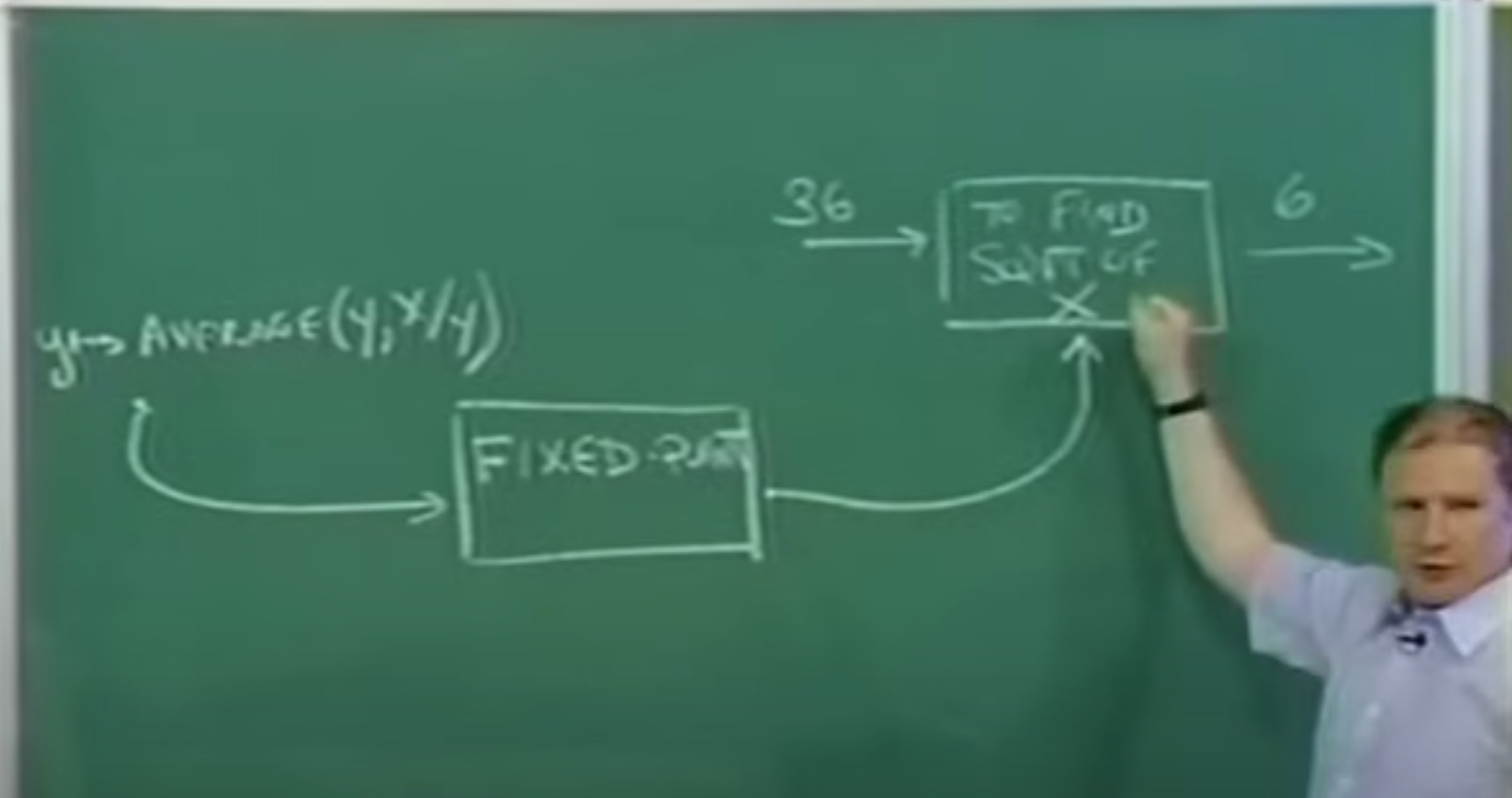

Seventeen minutes into Lecture 1A, Harold Abelson draws this on the chalkboard:

Here's a simple rendering of what he's drawn:

+-----------+

| to find |

36 -->| sqrt |--> 6

| of x |

y -> average(y,x/y) +-----------+

| ^

| +-------------+ |

+---->| fixed-point |-----+

+-------------+Note that the fixed-point box here represents a "higher order" function.

His commentary on this goes as follows:

"This fixed point box is such that if I input to it the function that takes Y to the average of Y and X/Y, then what should come out of that fixed point box is a method for finding square roots.

So in these boxes we're building, we're not only building boxes that you input numbers and output numbers, we're going to be building boxes that, in effect, compute methods, like finding square roots. And might take as their input functions, like Y goes to the average of Y and X/Y.

The reason we want to do that, the reason this is a procedure, will end up being a procedure, as we'll see, whose value is another procedure, the reason we want to do that is because procedures are going to be our ways of talking about imperative knowledge."

Boom. That's how fundamental this idea is.

- ← Previous

TASC Notes - Part 5 - Next →

TASC Notes - Part 6