Living on a narrowboat - embracing constraints

Previous post in this series: Working from a narrowboat - Internet connectivity.

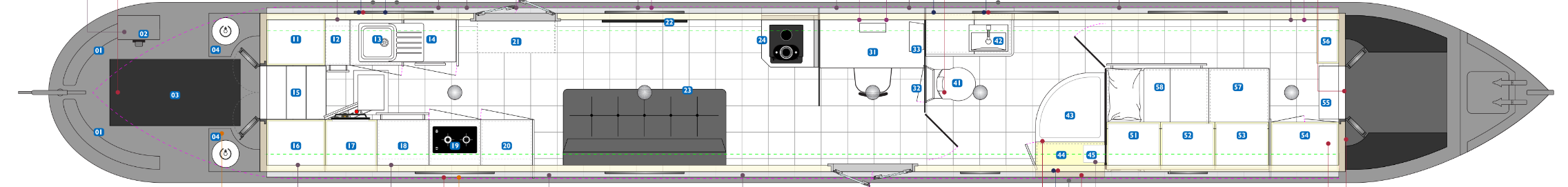

It's no secret that a narrowboat is smaller than the vast majority of land-based homes (or offices for that matter). In the first post in this series, I'm moving onto a narrowboat, I outlined some of the basic dimensions (57 feet long and 6 feet 10 inches wide) and shared a diagram of the narrowboat layout:

What's clear from the design is that given the outside space at the bow and the stern, the total internal cabin length is actually more like 42 feet, from the steps down into the galley from the double doors on the cruiser stern, all the way to the step up from the bedroom, through the double doors at the front, into the well deck at the bow (remember, each of the squares in the diagram represents 1 foot x 1 foot or 30 cm x 30 cm).

That's clearly a constraint that one cannot ignore. But it's not the most significant one. More importantly, constraints are not necessarily a bad thing anyway.

Small space, big picture

Let me pause here and dwell on something Igor Stravinsky said:

"The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one's self. And the arbitrariness of the constraint serves only to obtain precision of execution."

This is a great way to look at constraints, especially in today's world of everything everywhere at any time. While I've lived in very comfortable properties, I've never really been one that has coveted the new thing, the better washing machine, another car, that kind of thing. Yes, I've probably bought too much tech equipment in the past, but I've been offloading a lot of that via eBay, Gumtree and the like. What Stravinsky might have had in mind was certainly unlikely to be related to household appliances or computers, but the idea of material possession does come into it, at least from my perspective.

I mean, I'm not going to turn into a hermit or anything like that but over the past few years I've been conscious of how I live.

Reducing one's reliance on material possessions is one thing (and a useful one given the prospect of moving onto a narrowboat) but the feeling of freedom, or at least the ability to escape from the hamster wheel of consumerism is very attractive.

Living day to day with far fewer items holds an appeal for me that is hard to put into words. It's not that I'm eschewing all luxuries, it's that I am (and have to be) very particular about the few that I can allow myself. One of these is a space for my coffee making equipment.

If you open the narrowboat design diagram in a new window to see it in its full size, you will see a worktop in the galley, numbered 18, with drawers below. That's where this coffee making equipment is going to live.

Cooking and the multifuel stove

And while we're there, note the gas hob has just two burners. On many liveaboard narrowboats, there will be a full size cooker with four gas burners. While I've used all four burners while cooking for a load of dinner guests round at the house, that doesn't happen very often and as I'm going to be cooking just for myself for most of the time, two is all I need. What's more, there's the multifuel stove (numbered 24) that also will do perfect double duty for cooking as well as heating.

I want to write a separate post about what stove I chose, how I came to the decision and the factors I considered. For now, here's a picture of it:

It's from Chilli Penguin Stoves not too far away in Pwllheli, Wales, and is the Fat Penguin (Tall Order) model. As you can see, it has a decent oven and also the top of the stove acts as a hotplate too, for slow cooking, and brewing coffee in a moka pot.

This is in addition to the gas oven and grill I'll have in the galley below the two burner hob.

Gas

The hob, oven and grill all run on gas. So where's that from? If you look closely at the stern in the narrowboat design diagram, you'll see a couple of areas numbered 04. These are the stern gas lockers, and you can get a better idea of what they look like from these pictures.

In this first one, you can see inside them (they go deeper than they look):

In this one, you can see that their effective height from the stern floor is such that they make nice seats:

The gas is LPG and usually propane, and is most commonly found in 13kg canister sizes. The lockers are designed to take a 13kg canister each. You can read more about gas on board in this article Gas (LPG) On Narrowboats on The Fitout Pontoon's website.

So in a liveaboard situation, you're effectively off grid. And this is a constraint that's hard to ignore. Once you've got your two gas canisters, and you're underway on the cut, that's it. No unlimited supply. To be fair, even when you're in a marina, on a long term mooring, you'll still have to change the canisters when they're empty (this is why having two instead of one is a great idea).

Incidentally, David Johns, otherwise known as the person behind the YouTube channel CruisingTheCut has a video on fuel boats, those traders who ply the waterways carrying coal, diesel and LPG. They have schedules and you can buy from them as they come round your area. The video is A day in the life of a fuel boat on the UK canals.

Water

Talking of being off grid, you're not only going to be carrying your entire gas supply, but also your water. Again, without going into too much detail right now, narrowboats have water tanks that hold water for your everyday use. As well as for drinking, it's for washing, showering, and the toilet (yes there are composting toilets but that's a subject for another time and I'm not going for one of those anyway, as I don't fancy the process of managing multiple stages of composted waste in bags on my narrowboat, thank you very much).

These tanks are often at the bow, under the well deck, and while there are different types (and some used to be part of the hull itself), modern narrowboats will often be fitted with tanks made of stainless steel, holding between 400 and 500 litres. Once that water's gone, it's gone. Another constraint, and this time perhaps an even more important one than the gas constraint.

There are water points that can be found everywhere along the canal network, so yes you can obviously fill your tank up again, but again, it's not like the cold water tap in a house, which has a magically endless supply. You have to use your water carefully and plan where and when you can get more.

You can see the space for the water tank in this picture; it will go directly behind the bow thruster tube (which will run between the two exit holes on each side) and sit underneath the well deck.

During the steelwork, Mark from the Fitout Pontoon contacted the team and got them to cut the exit holes as far forward as possible, to leave more room for a larger tank. Normally the exit holes would be a bit further back; in fact, you can see the original planned position for the bow thruster tube, indicated by the arrows marked on the base plate:

Electricity and fuel for the engine and for the stove

It's clear that a narrowboat life means an off grid life, for the most part. I say for the most part, as some folks live on their narrowboats which are permanently moored, and are thus also able to be permanently connected to "shoreline power" (i.e. a 230 volt AC supply).

But if you're not permanently moored, you have further constraints, including where your electricity comes from, and how much diesel you can store, and what you need to use it for. I want to cover power, engine and heating in separate posts, but here's a quick overview for now.

Diesel

Diesel is used for propulsion (i.e. there's a diesel engine) and for heating. There's a diesel tank in the stern, built in to the shell. You can see where it is in this photo (marked with the red oblong) which also shows the diesel tank drain (the arrow on the right) and three pipes marked E, F and R.

Regarding those three pipes and their legends:

- "E" stands for Eberspaecher and is one of two common manufacturers of diesel powered heating systems for marine application. I'm actually having one from Webasto, the other common manufacturer. But basically this pipe marked "E" is to supply diesel to that heating system (which in turn will service a radiator circuit in the cabin, and in addition the pipes in the circuit will run through a hot water tank, called a calorifier).

- "F" stands for flow, i.e. the supply of diesel from the tank to the engine (to provide not only propulsion but also, via the alternator, to provide charge to the leisure batteries and starter battery, in addition to charging them from solar panels).

- "R" stands for return, and is to allow the return of unused diesel from the engine back into the tank. To be honest, it was only after attending a recent two day Diesel Engine and Boat Maintenance Course at the Narrowboat Skills Centre that I learned how this worked and why it was necessary.

The phrase "leisure batteries" refers to the battery bank that is used to power everything on and inside the narrowboat. It is used to contrast with "starter battery" which is the one that is used to start the engine; they are usually on separate circuits so that even if you drain your leisure batteries through use of equipment on board, you can always start your engine (and then in turn recharge the drained batteries).

Fuel for the stove

I can use coal and / or wood for the multifuel stove. But therein lies yet another constraint. Where do I keep it? There's a finite amount of space to store things. Often narrowboaters will store bags of coal on the roof (if space allows, and if you're not that bothered about the paintwork) or in the bow area, both in the well deck and also in what is still traditionally called the gas locker at the front.

You can see this bow gas locker in the narrowboat design diagram, specifically its lid, and you can see the (square) hole that the lid covers in the picture of the bow, above. You can get a decent amount of coal and wood in there, but the space is finite and there are other bulky things that need space in there - the bow thruster itself, a hosepipe reel (for bringing water from the water point taps and into the tank), and so on.

Again, embracing that constraint, using fuel wisely and conservatively, and planning where & when you're going to be able re-stock, is key.

Electricity

This is such a huge subject I'm going to say very little at this stage, and leave the detail for another time. Suffice it to say that given that I'll be not only living aboard, but working aboard too (see Working from a narrowboat - Internet connectivity).

I'll be moored up and at my desk for large chunks of the day. At my desk I'll have a laptop, an external monitor, and the other usual devices associated with working (and live streaming from) home.

I'll also be running a fridge / freezer, lights, and so on. After consulting with Mark I made the decision to go for a system that is predominantly 230 volt (AC). In other words, I can use all normal appliances on board. But for that, I will need an inverter (which itself consumes a small amount of power to run) to turn the DC from the leisure battery bank to AC. And the charge in my batteries will definitely not be limitless!

So I will have to think about electricity a lot. How I use it, how I maintain the batteries and the rest of the system, and how I put charge back into the batteries.

Constraints may maketh me

That's a lot of constraints. Ones that I cannot easily work around, or avoid.

Nor do I want to. Living more frugally, more consciously, from an environment perspective, can only be a good thing. And the limitations and restrictions that come as a natural part of living in a small off grid space such as a narrowboat keeps me away from the dangers of that age old truism - the more you have, the more you want, and the further out of reach satisfaction becomes.

Age and life experience has made me realise that one of the most precious commodities is time. And the wonderful thing one comes to realise here is that amidst all the constraints that I've described here, one thing that is no more constrained than before, is time.

In fact, through that very increased and pronounced contrast, I'm hoping that I will come to value and enjoy time as an end in itself. On the canal, things move slowly. Very slowly. And I think that is reflected in how time will continue to be available in the same quantities as ever, despite everything else being less available, less copious, and far more immediately finite.

A possible net result of this can be a greater awareness and appreciation for the small things, for the simple things. And that's something I would cherish.

Next post in this series: Living on a narrowboat - the stove as the heart of the home.