Learning by rewriting - bash, jq and fzf details

One of the ways I learn is by reading and sometimes rewriting other people's scripts. Here I learn more about jq by rewriting a friend's password CLI script.

My friend Christian Drumm published a nice post this week on Adapting the Bitwarden CLI with Shell Scripting, where he shared a script he wrote to conveniently grab passwords into his paste buffer at the command line.

It's a good read and contains some nice CLI animations too. In the summary, Christian remarks that there may be some areas for improvement. I don't know about that, and I'm certainly no "shell scripting magician" but I thought I'd have a go at modifying the script to perhaps introduce some further Bash shell, jq and fzf features to dig into.

Emulating the CLI

I don't have Bitwarden, so I created a quick "database" of login information that took the form of what the Bitwarden CLI bw produced. First, then, is the contents of the items.json file:

[

{ "name": "E45 S4HANA 2020 Sandbox", "login": { "username": "e45user", "password": "sappass" } },

{ "name": "space user", "login": { "username": "spaceuser", "password": "in space" } },

{ "name": "foo", "login": { "username": "foouser", "password": "foopass" } },

{ "name": "bar", "login": { "username": "baruser", "password": "sekrit!" } },

{ "name": "baz", "login": { "username": "bazuser", "password": "hunter2" } }

]Then I needed to emulate the bw list items --search command that Christian uses to search for an entry. As far as I can tell, it returns an array, regardless of whether a single entry is found, or more than one. I'm also assuming it returns an empty array if nothing is found, but that's less important here as you'll see.

I did this by creating a script bw-list-items-search which looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Emulates 'bw list items --search $1'

jq --arg name "$1" 'map(select(.name | test($name; "i")))' ./items.jsonPerhaps unironically I'm using jq to emulate the behaviour, because the data being searched is a JSON array (in items.json). I map over the entries in the array, and use the select function to return only those entries that satisfy the boolean expression passed to it:

.name | test($name; "i")This pipes the value of the name property (e.g. "E45 S4HANA 2020 Sandbox", "space user", "foo" etc) into the test function which can take a regular expression, along with one or more flags if required.

Here, we're just taking the value passed into the script, via the argument that was passed to the jq invocation with --arg name "$1". This is then available within the jq script as the binding $name. The second parameter supplied here, "i", is the "case insensitive match" flag.

The result means that I can emulate what I think bw list items --search does:

; ./bw-list-items-search e45

[

{

"name": "E45 S4HANA 2020 Sandbox",

"login": {

"username": "e45user",

"password": "sappass"

}

}

]Here's an example of where more than one result is found:

; ./bw-list-items-search ba

[

{

"name": "bar",

"login": {

"username": "baruser",

"password": "sekrit!"

}

},

{

"name": "baz",

"login": {

"username": "bazuser",

"password": "hunter2"

}

}

]The main script

Now I could turn my attention to the main script. Here it is in its entirety; I'll describe it section by section.

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

pbcopy() { true; }

copy_uname_and_passwd() {

local login=$1

echo "> Copying Username"

jq -r '.username' <<< "$login"

echo "> Press any key to copy password..."

read

echo "> Copying Password"

jq -r '.password' <<< "$login"

}

main() {

local searchterm=$1

local selection logins

logins="$(./bw-list-items-search $searchterm)"

selection="$(jq -r '.[] | "\(.name)\t\(.login)"' <<< "$logins" \

| fzf --reverse --with-nth=1 --delimiter="\t" --select-1 --exit-0

)"

[[ -n $selection ]] \

&& echo "Name: ${selection%%$'\t'*}" \

&& copy_uname_and_passwd "${selection#*$'\t'}"

}

main "$@"Overall structure and the main function

For the last few months, my preference for laying out non-trivial scripts has been to use the approach that one often finds in other languages, and that is to define a main function, and right at the bottom, call that to start things off.

This call is main "$@" which just passes on any and all values that were specified in the script's invocation - they're available in the special parameter $@ which "expands to the positional parameters, starting from one" (see Special Parameters).

The main function

I like to qualify my variables, so use local here, which is a synonym for declare. I wrote about this in Understanding declare in case you want to dig in further.

Because I have my emulator earlier, I can make almost the same-shaped call to the Bitwarden CLI, passing what was specified in searchterm and retrieving the results (a JSON array) in the logins variable.

Next comes perhaps the most involved part of the script, which results in a value being stored in the selection variable (if nothing is selected or available, then this will be empty, which we'll deal with too).

Determining the selection part 1 - with jq

The value for selection is determined from a combination of jq and fzf, which are also the two commands that Christian uses.

This is the invocation:

jq -r '.[] | "\(.name)\t\(.login)"' <<< "$logins" \

| fzf --reverse --with-nth=1 --delimiter="\t" --select-1 --exit-0The first thing to notice is that I'm using <<< which is a here string - it's like a here document, but it's just the variable that gets expanded and fed to the STDIN of the command. This means that whatever is in logins gets expanded and passed to the STDIN of jq.

Given the emulation of the Bitwarden CLI above, a value that might be in logins looks like this:

[

{

"name": "bar",

"login": {

"username": "baruser",

"password": "sekrit!"

}

},

{

"name": "baz",

"login": {

"username": "bazuser",

"password": "hunter2"

}

}

]Let's look at the jq script now, which is this:

.[] | "\(.name)\t\(.login)"This iterates over the items passed in (i.e. it will process the first object containing the details for "bar" and then the second object containing the details for "baz") and pipes them into the creation of a literal string (enclosed in double quotes). This literal string is two values separated with a tab character (\t) ... but those values are the values of the respective properties, via jq's string interpolation).

It's worth noting that the value of .name is a scalar, e.g. "bar", but the value of .login is actually an object:

"login": {

"username": "baruser",

"password": "sekrit!"

}but this gets turned into a string. If "bar" is selected, then the value in selection will be:

bar {"username":"baruser","password":"sekrit!"}where the whitespace between the name "bar" and the rest of the line is a tab character.

So given the two values (for "bar" and "baz") above which would have been extracted for the search string "ba", the following would be produced by the jq invocation:

bar {"username":"baruser","password":"sekrit!"}

baz {"username":"bazuser","password":"hunter2"}Note that the -r option is supplied to jq to produce this raw output.

Determining the selection part 2 - with fzf

This is then passed to fzf, which is passed a few more options than we saw with Christian's script. Taking them one at a time:

--reverse- this is the same as Christian and is a layout option that causes the selection to be displayed from the top of the screen.--delimiter="\t"- this tellsfzfhow the input fields are delimited, and as we're using a tab character to separate the name and login information, we need to tellfzf(using just spaces would give us issues with spaces in the values of the names).--with-nth=1- this says "only use the value of the first field in the selection list", where the fields are delimited as instructed (with the tab character here). This means that only the value of the "name" is presented, not the "login" (username and password) details.--select-1- this tellsfzfthat if there's only one item in the selection anyway, just automatically select it and don't show any selection dialogue.--exit-0- this tellsfzfto just end if there's nothing to select from at all (which would be the case if the invocation tobw list items --searchreturned nothing, i.e. an empty array).

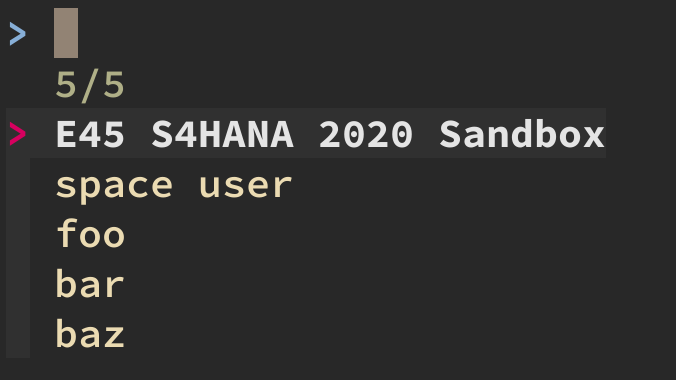

Here's what the selection looks like if no search string is specified, i.e. it's a presentation of all the possible names:

Once we're done with determining the selection, we check to see that there is actually a value in selection and proceed to first show the name and then to call the copy_uname_and_passwd function.

Displaying the name and extracting the login details

It's worth highlighting that while fzf only presents the names in the selection list, it will return the entire line that was selected, which is what we want. In other words, given the selection in the screenshot above, if the name "E45 S4HANA 2020 Sandbox" is chosen, then fzf will emit this to STDOUT:

E45 S4HANA 2020 Sandbox {"username":"e45user","password":"sappass"}(again, remember that there's a tab character between the name "E45 S4HANA 2020 Sandbox" and the JSON object with the login details).

So to just print the name, we can use shell parameter expansion to pick out the part we want. The ${parameter%%word} form is appropriate here; this will remove anything with longest matching pattern first.

In other words, the expression ${selection%%$'\t'*} means:

- take the value of the

selectionvariable - look at the trailing portion of that value

- find the longest match of the pattern

$'\t'* - and remove it

The $'...' way of quoting a string allows us to use special characters such as tab (\t) safely. The * means "anything". So the pattern is "a tab character and whatever follows it, if anything".

So if the value of selection is:

E45 S4HANA 2020 Sandbox {"username":"e45user","password":"sappass"}then this expression will yield:

E45 S4HANA 2020 SandboxThe expression in the next line, where we invoke the copy_uname_and_passwd function, is ${selection#*$'\t'} which is similar. It means:

- take the value of the

selectionvariable - look at the beginning portion of that value

- find the shortest match of the pattern

*$'\t' - and remove it

This pattern, then, is "anything, up to and including a tab character".

Given the same value as above, this expression will yield:

{"username":"e45user","password":"sappass"}The copy_uname_and_passwd function

This is very similar to Christian's original script, except that we can use a "here string" again to pass the value of the login variable to jq each time. Given what we know from the main function, this value will be something like this:

{"username":"e45user","password":"sappass"}which makes for a simpler extraction of the values we want (from the username and password properties).

The pbcopy function

While my main machine is a macOS device, I'm working in a (Linux based) dev container and therefore don't have access right now to the pbcopy command. As I wanted to leave calls to it in the script to reflect where it originally was, this function that does nothing will do the trick.

Wrapping up

There's always more to learn about Bash scripting and the tools we have at our disposal. And to use one of the sayings from the wonderful Perl community - TMOWTDI - "there's more than one way to do it". I'm sure you can come up with some alternatives too, and some improvements on what I've written.

Keep on learning and sharing.