The Observer's Book of JS Style

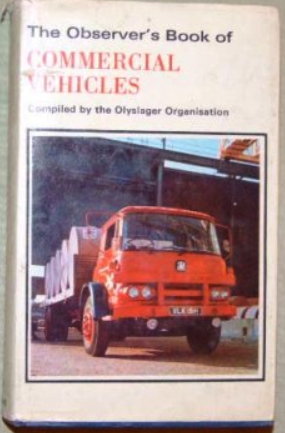

In the 1970's I had a book which I cherished: The Observer's Book of Commercial Vehicles. It was pocket-sized & well thumbed, and listed various vans and trucks. I could identify a Volvo F88 tractor unit from 500 paces.

I guess the interest in spotting and identifying things of interest has never left me, and so I find myself delighting in various examples of style with respect to expressing oneself in code. These days it's mostly in the context of JavaScript; unlike other languages, JavaScript is not only multi-paradigm but extremely malleable, making it possible to leave behind a trace of one's character, often by accident.

This post is to record some of those characterful or otherwise interesting expressions in code, taken predominantly from the Node.js codebase for the SAP Cloud Application Programming (CAP) Model.

File: @sap/cds/server.js

Who knew there could be so much richness to write about in a single file of fewer than 100 lines? This is the main server mechanism, in the form of a server.js file in @sap/cds, that uses the Express web framework to serve resources both static and dynamic.

If you want to see this code in context, or even get it running in your favourite debugging setup to examine things step by step, pull the @sap/cds package from SAP's NPM registry, dig in to the sources, and have a look.

Object destructuring with default value

const { PORT=4004 } = process.env

return app.listen (PORT)This is a lovely example of object destructuring in action, with a bonus application of the default values option. Plus of course the appropriate use of a constant. This takes whatever value the PORT environmental variable might have, falling back to a default of 4004 if a value wasn't set.

The other thing that stands out to me is a particular affectation that I'm still not sure about - the use of whitespace before the brackets in the app.listen call. It does make the code feel more like a spoken language, somehow; here's another example of that use of whitespace from the same file:

await cds.serve (models,o) .in (app)I think I like it.

Ignored parameters

app.get ('/', (_,res) => res.send (index.html)) //> if none in ./appThe use of the undercore (_) here is not particular to JavaScript nor uncommon, but it's nice to see it in use here. As a sort of placeholder for a parameter that we're not interested in using in the function that is passed to app.get, the underscore is for me the perfect character to use.

If you're familiar with HTTP server libraries, you'll be able to guess what that parameter is that is being ignored. An HTTP handler function is usually passed the incoming HTTP request object, and the fledgling HTTP response object. The response object is the only thing that is important here, so the signature is

(_,res) => ...rather than

(req,res) => ...Getter and fake filename

Did you notice something odd in that previous example? There was a call to res.send like this:

res.send (index.html)At first I was only semi-aware of something not quite right about the way that appeared. But then looking further down in the code, I suddenly realised. index.html is not a filename ... it's a property (html) on an object (index)! Further down, we come across this, where it's defined:

const index = { get html() {

...

return this._html = `

<html>

<head>

...

`

}}I've not seen the use of a getter in the wild that often. According to the MDN web docu on 'getter':

"The get syntax binds an object property to a function that will be called when that property is looked up".

Put simply, you can define properties on an object whose values are dynamic, resolved by a call to a function. Of course, you can also define functions as property values, but that would mean that you'd have to use the call syntax, i.e. index.html() in this case. But given the emphasis on something that's more readable than normal, I can see why a getter was used here. Although I think it might take a bit of getting used to.

More destructuring

Now the cat is out of the bag, it gets everywhere! I wanted to include this example of destructuring because at first I was scratching my head over the line, but then after staring at it for a few seconds I realised what I was looking at.

const { isfile } = cds.utils, {app} = cds.env.folders, {join} = require('path')

const _has_fiori_html = isfile (join (app,'fiori.html'))(I'm including the second line only to give a bit of usage context).

Part of the reason this had me wondering was simply due to the whitespace - I guess the author was in a hurry as the spacing is not consistent. I thought there was something special about the first pair of braces around isfile, but in fact it's just three separate constant declarations, all on the same line: isfile, app and then join.

The value for each is resolved through destructuring. For example, the app constant comes from the cds.env.folders property which itself has a number of child properties, one of which is app. cds.env is part of CAP's Node.js API, and provides access to an effective environment computed from different layers of configuration.

Going one example further, the join constant ends up having the value of join in the Node.js builtin path package (the value is a function), as you can see in this snippet from a Node.js REPL session:

=> node

> require('path')

{ resolve: [Function: resolve],

normalize: [Function: normalize],

isAbsolute: [Function: isAbsolute],

join: [Function: join],

relative: [Function: relative],

...

Anyway, while there's more to explore and pore over, I'll leave it here for now. Who knows, I may write another one of these covering more finds in the source code. If you're interested, let me know.