Monday morning thoughts: mainframes and message documentation

In this post, I think about mainframes and a message documentation aspect from the mainframe world that, while originally proprietary, is a big plus for operators and developers alike and something I'd love to see return.

On my route into Manchester for Saturday's run with the Mikkeller Running Club Manchester chapter I listened to an InfoQ interview: Adrian Cockcroft on Microservices, Terraservices [sic] and Serverless Computing. From 2016, it's a great interview conducted by Wesley Reisz, and contains much to ponder even today.

Teraservices and mainframes

One of the subjects covered was "teraservices", starting around 17 minutes into the audio recording. I didn't really know what they were until Adrian explained; basically, they're services at the opposite end of the scale to microservices. You know the sort of thing:

smaller -- pico nano micro milli ~~ kilo mega giga tera -- largerThe irony of the misspelling in the InfoQ title makes me smile - the word "terra" (rather than tera) means ground, or earth in Latin, which couldn't be further from where these services have their home - in the cloud.

Teraservices run in memory sizes far greater than microservices. Adrian made the comparison between microservices running in 100 megabytes of RAM and teraservices running in 2 terabytes of RAM, on machines available by the hour on Amazon Web Services.

I'd like to think that the advent of in-memory data storage and processing with HANA and the corresponding demand for machines with super large memory footprints has pushed the industry to the point where terabyte-sized machines are available as commodities in the cloud today. Adrian and Wesley laughed about things turning full circle (towards the mainframe era) and running a whole bunch of services on one "great hulking machine". Making effective use of such a machine would involve using the internal memory as a communications backplane between all the containers running in that machine, a backplane much faster than any network-based backplane would allow.

And yes, it does remind me* of the mainframe era in general. But more specifically, making best use of specialised hardware for giant workloads is what mainframes are all about.

*Of course, I've written about the mainframe era before, when thinking about web terminals and the cloud in general in an earlier post in this Monday morning thoughts series: "upload / download in a cloud native world", and way back beyond then too: "Mainframes and the cloud - everything old is new again".

I read somewhere that the computing industry* cycle is at the decade scale - in other words, ideas and concepts come around and are (re)invented every ten years or so. I think the cycle is a little longer than that, but a cycle does exist. On the one hand, mainframes never really went away - they're still handling a large part of the world's transactional processing in specific sectors such as banking and airline industries. On the other hand, the conscious shift away from mainframes in enterprise computing in the early 90's is now perhaps being reflected, like an echoing musical phrase that comes later in the piece, by a move to the cloud ... perhaps it's fair to say that the general idea of mainframes are back, albeit in a different guise.

*and not just the computing industry - companies today are looking at "insourcing", where a decade ago they were falling over themselves to outsource a lot of their processes.

The IBM documentation machine

After leaving university in 1987 I started work at Esso Petroleum in London, and joined the Database Support Group. Esso was an IBM mainframe shop (I'd *just missed* the punched card era, which was a shame, on reflection) and in the data centre, sixty miles away out in Abingdon, Oxfordshire, there were IBM 3090 series mainframes running version of MVS - first MVS/XA and then MVS/ESA. While the machines were remote, the documentation was local, in the form of huge printed tomes that hung from their spine on a rack system, in a special documentation room.

I have visceral memories of spending time in that room, selecting the right tome, carefully unhooking it from the rack (they were usually hundreds of pages each and quite heavy), opening it up on the desk and finding, invariably, exactly what I was looking for. Then getting sidetracked and spending more time than my initial investigations required me to, looking through related documentation and, discovering new worlds of related information.

Message identification and documentation

What I remember the most though is how thoroughly messages were documented. Not just that, but how the messages were actually organised and catalogued. Messages were issued on consoles, and in batch job log output, for example, and each message was prefixed with the message ID, identifying the subsystem, the actual message number and the severity. Over time, I found myself being able to just glance at the "pattern" of messages in a job log, and discern, without much further investigation, what had happened.

Even more impressive - and useful - than just the consistent identification of messages was the actual message documentation itself. Taking a printout of a job log, say, to the documentation room, I'd reach for one of the MVS system messages volumes and look up the documentation for the message identification specified. I'd find not just a rehashing of the message line, in a different format, but a decent and full description, thoughtfully and accurately written, and where there was relevant action required, an explanation of what we needed to do.

My memory might be rose-tinted today, but I honestly can't think of an area of IBM big iron computing in that facility that was a mystery. Everything that happened was described in messages, every message was identified, and every identified message was documented in great detail.

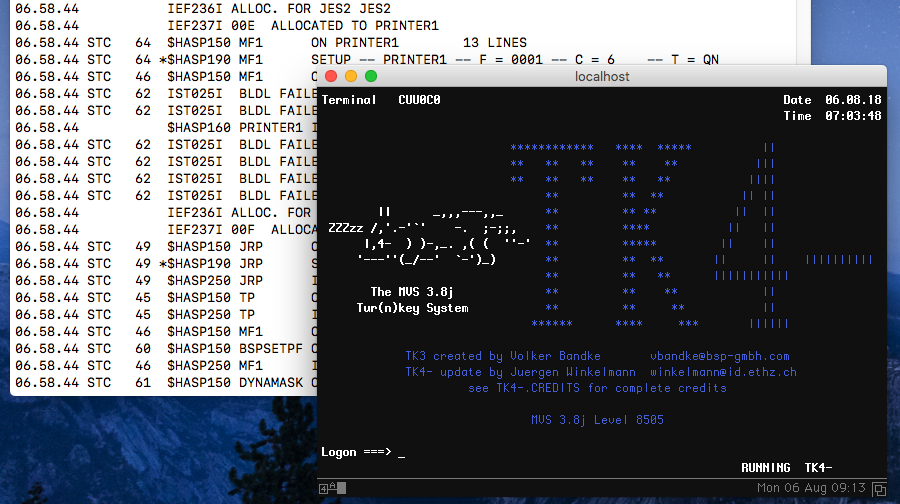

I've recently started carving out a little bit of time again for Hercules, the open source System/370, ESA/390, and z/Architecture emulator (I've played around with Hercules before: see the post Turnkey MVS 3.8J on Hercules S/370 Screenshot from 2005).

More specifically, I've been looking at Juergen Winklemann's TK4- turnkey distribution of MVS 3.8j (a version of MVS that is now in the public domain). I powered up an emulated 3033 IBM mainframe and watched the Initial Program Load (IPL) sequence on the console before logging in.

Messages in an unattended console of an emulated IBM 3033 mainframe, and a connected 3270 session

Here's a really simple example of what I mean about message identification and documentation. Looking at the first two messages at the top of the display in the screenshot, we have:

IEF236I ALLOC. FOR JES2 JES2

IEF237I 00E ALLOCATED TO PRINTER1Both message identifiers show that the messages belong to the IEF family, which is for events relating to IPL, Job Entry Subsystem (JES) and scheduler services, and more (see the z/OS Message Directory for more information). We're pointed to the system messages volume 8 (IEF-IGD), the older equivalent of which would have been hanging in that documentation room all those decades ago.

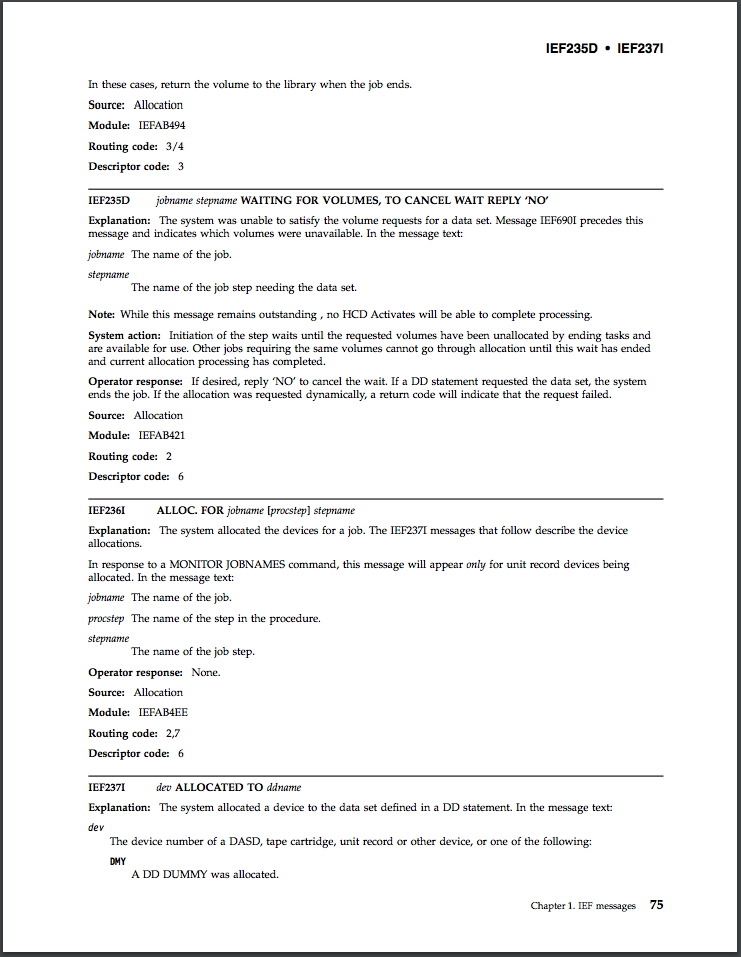

This is the page from the volume that contains documentation for IEF236I:

Just look at the richness and precise nature of the information on that page. That volume (IEF-IGD) is almost 1000 pages in length, by the way.

You can imagine that with some patience, a desire to master the very explicit skill of navigating & using the IBM documentation, and some naus, there were few problems that occurred that you couldn't fathom. Everything was there, if you only took the time to find it and read it.

A proprietary plus

One of the reasons why this was possible, of course, was because IBM dominated the market, and was large enough to cause customers to buy wall-to-wall IBM hardware and software. "No-one got fired for buying IBM" was the phrase. Their dominance and size & breadth of offerings made it possible to produce such a wonderfully rich layer of information, the likes of which I have never seen since, not even close.

The proprietary nature of that era meant that everything that one did as an operator, systems programmer or developer was within the context of what IBM produced. The word "proprietary" has now taken on negative tones, and there are good reasons for that. But I'd posit that one big plus from the proprietary circumstances in this age was that this was documentation done right. It shows that it's possible to build complex systems and subsystems and make them understandable at an operations level. One could argue, as well, that message documentation was more important when the source code wasn't available. But the availability of source code only helps a small percentage of those working with systems like this, and doesn't excuse good documentation.

Today's open source world is wonderful and a major reason why we've progressed so much in terms of computing, research and enterprise. The nature of open source means, indirectly, that the kind of documentation that existed for the complex array of subsystems of an IBM facility is unlikely to be produced for the systems that we're building today. We take best of breed products, tools and processes and glue them together, and it's more or less guaranteed that the operator surface area is so disparate and disconnected that a uniform -- dare I say ivory tower -- approach to consistent documentation, even a consistent way to output and identify error messages, is not going to happen without some sort of massive concerted effort.

One other thing that only occurred to me this morning while writing this - the messages being output on the console of my emulated 3033 mainframe from decades ago are documented in modern PDF-based files for IBM's z/OS series. They are the same messages, and are still relevant today. Now if that's not solid consistency I don't know what is.

I yearn for the days when messages were consistent, easy to identify and read, and were documented to within an inch of their life. It's one aspect of the first mainframe era that I'd love to see revived in the second mainframe era. What's not to like?

This post was brought to you by today's quiet run in the dawn light that rose on a new week, and by the happy nostalgia that looking through old IBM documentation (available at bitsavers) brings.

Read more posts in this series here: Monday morning thoughts.