Forget SOAP - build real web services with the ICF

I don’t like getting into a lather when it comes to data and function integration. Rather than using SOAP, I prefer real web services, built with HTTP.

As an example of taking the RESTian approach to exposing your SAP data and functionality through services you can build with the excellent Internet Communication Framework (ICF) layer, I thought I’d show you how straightforward and natural data integration can be by using a spreadsheet as an example.

In my recent SDN article (published this week) Real Web Services with REST and ICF I presented a simple ICF handler example that allowed you to directly address various elements of CTS data (I prototyped it in my NW4 system so I thought I’d use data at hand, and build an example that you could try out too). For instance, you could retrieve the username of the person responsible for a transport by addressing precisely that data element like this:

http:/qmacro/transport/NW4K900007/as4textThe approach of making your SAP data and functionality first class web entities, by giving each element its own URL, has wide and far reaching benefits.

Take a programmable spreadsheet, for example. You’re managing transports between systems by recording activity in a spreadsheet. You’re mostly handling actual transport numbers, but have also to log onto SAP to pull out information about those transports. You think: “Hmmm, wouldn’t it be useful if I could just specify the address of transport XYZ’s user in this cell here, and then the value would appear automatically?”

Let’s look at how this is done. My spreadsheet program of choice is the popular Gnumeric, available on Linux. If you use another brand, no problem – there’s bound to be similarities enough for you to do the same as what follows. For background reading on extending Gnumeric with Python, you should take a look here.

With Gnumeric, you can extend the functions available by writing little methods in Python. It’s pretty straightforward. In my home directory, I have a subdirectory structure

.gnumeric/1.2.1-bonobo/plugins/myfuncs/where I keep the Python files that hold my personal extended methods.

In there, in a file called my-funcs.py, I have a little script that defines a method func_get(). This method takes a URL as an argument, and goes to fetch the value of what that URL represents. In other words, it performs an HTTP GET to retrieve the content. If successful, and if the value is appropriate (it’s just an example here, I’m expecting a text/plain result), then it’s returned … and the cell containing the call to that function is populated with the value.

Here’s the code.

# The libs needed for this example

import Gnumeric

import string

import urllib

from re import sub

# My version of FancyURLopener to provide basic auth info

class MyURLopener(urllib.FancyURLopener):

def prompt_user_passwd(self, *args):

return ('developer', 'developer')

# The actual extended function definition

def func_get(url):

urllib._urlopener = MyURLopener()

connection = urllib.urlopen(url)

data = connection.read()

if connection.info().gettype() == 'text/plain':

return sub("

$", "", data)

else:

return "#VALUE!"

# The link between the extended function name and the method name

example_functions = {

'py_get': func_get

}It’s pretty straightforward. Let’s just focus on the main part, func_get(). Because the resource in this example is protected with basic authentication (i.e. you have to supply a username and password), we subclass the standard FancyURLopener to be able to supply the username and password tuple, and then assign an instance of that class to the urllib._urlopener variable before actually making the call to GET.

If we get some ‘text/plain’ content as a result, we brush it off and return it to be populated into the cell, otherwise we return a ‘warning – something went wrong’ value.

We add the method definition to a hash that Gnumeric reads, and through the assignment, the func_get() is made available as new custom function py_get in the spreadsheet. (There’s also an extra XML file called plugin.xml, not shown here but described in the Gnumeric programming documentation mentioned earlier, that contains the name of the function so that it can be found when the spreadsheet user browses the list of functions.)

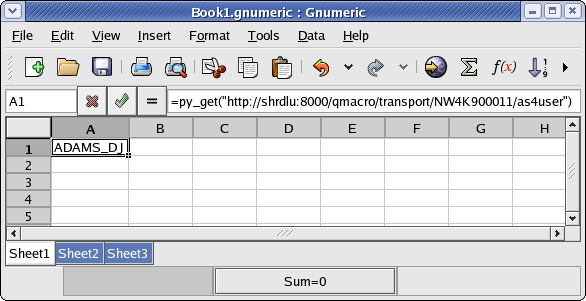

So, what does that give us? It gives us the ability to type something like this into a spreadsheet cell (split for readability):

=py_get('http://shrdlu.local.net:8000/qmacro/transport/NW4K900011/as4user')and have the cell automagically populated with the appropriate data from SAP. You can see an example of this in action in the screenshot:

As you can see, being able to address information as first class web resources opens up a universe of possibilities for the use of real web services.

As a final note, I’ve submitted a SAP TechEd talk proposal. It’s titled:

“The Internet Communication Framework: Into Context and Into Action!”

If you’re interested in learning more about the ICF, and want to have some fun building and debugging a simple web service with me, you know where to cast your vote if you haven’t already. Hurry though – there’s only a few hours to go!

Thanks!

Originally published on SAP Community

- ← Previous

Real Web Services with REST and ICF - Next →

TechEd talk winners - congrats